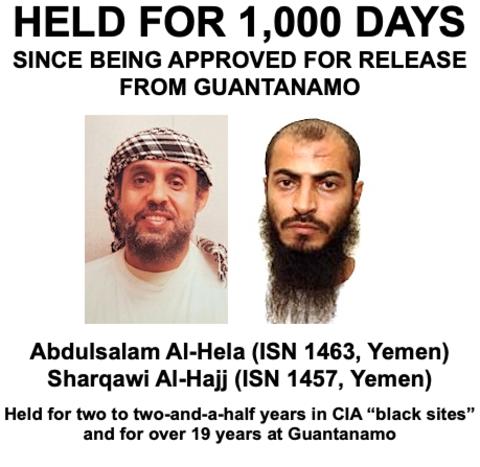

Held for 1,000 Days Since Being Approved for Release from Guantánamo: Abdulsalam Al-Hela and Sharqawi Al-Hajj

Abdulsalam al-Hela, photographed at Guantánamo in recent years, and Sharqawi al-Hajj, in a photo included in his classified military file, released by WikiLeaks in 2011.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout 2024. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, March 4, 2024

This is the fourth in a new series of ten articles, alternately posted here and on my own website, telling the stories of the 16 men still held at Guantánamo (out of 30 men in total), who have long been approved for release from the prison, but have no idea of when, if ever, they will actually be freed.

These 16 men were all unanimously approved for release by high-level U.S. review processes, established by President Obama, and consisting of representatives of the Departments of Justice, Defense, State and Homeland Security, as well as the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and yet they are still held because the reviews were purely administrative, and no legal mechanism exists that can compel the U.S. government to free them, if, as is apparent, senior officials are unwilling to prioritize their release.

There is a complication. Most, if not all of these men can’t be repatriated, because, since the early days of the Obama administration, Republicans have inserted provisions into the annual National Defense Authorization Act preventing the repatriation of prisoners to proscribed countries, including Yemen, where most of these men are from.

However, in August 2022, President Biden belatedly appointed an official in the State Department — former ambassador Tina Kaidanow — as Special Representative for Guantánamo Affairs, "responsible for all matters pertaining to the transfer of detainees from the Guantánamo Bay facility to third countries," and it is reasonable to assume that she has made some headway in locating a country prepared to resettle at least some of these men, but that efforts to actually free them have stalled because the Biden administration doesn’t want to upset a handful of Republican lawmakers who are fanatical in their support for Guantánamo’s continued existence, while he seeks the GOP’s cooperation in funding military support for Israel and Ukraine.

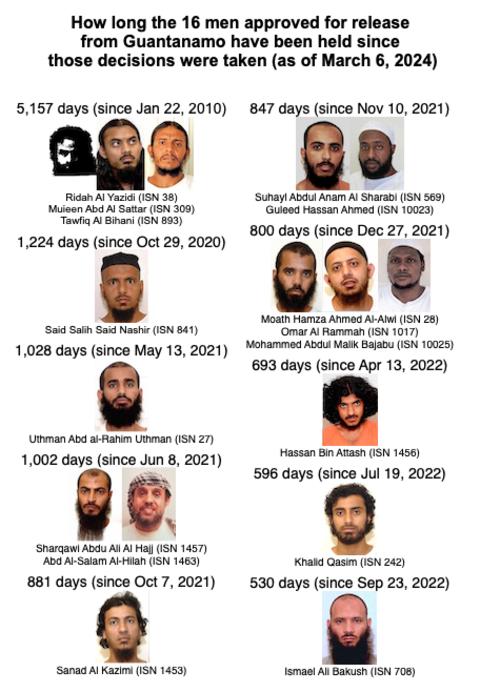

As of today, these 16 men have been held for between 528 and 1,222 days since being approved for release — and in three outlying cases for 5,155 days.

In the three articles to date, I’ve covered the stories of five of these men, including the three outliers, and today’s article features the stories of two men who were approved for release on June 8, 2021, but who, until that point, had been held at Guantánamo for nearly 17 years without charge or trial, having been brought there in September 2004 with seven other men, all of whom had been held and tortured for up to two and half years in CIA "black sites" or in proxy prisons run by foreign governments on the CIA’s behalf.

Sometimes identified as the "mid-value detainees," they were the only prisoners to arrive at Guantánamo between November 2003, when the arrival of "low-value detainees" (the majority of Guantánamo's population) ceased, and September 2016, when 14 "high-value detainees" were brought from CIA "black sites." However, despite the U.S. authorities’ sometimes strenuous efforts to suggest that these men were significant, five have been freed, without ever being charged, while the other four — also never charged — have been approved for release.

The story of Abdulsalam al-Hela

Abdulsalam al-Hela (ISN 1463), a Yemeni who is 56 years old, was a tribal leader — the sheikh for 10,000 people — and a highly successful businessman, who, as his attorney, Beth Jacob, described him in 2018, lived "a luxurious life, in a large house with servants," as a result of being "a natural entrepreneur" from a "well-to-do" family, who began with "construction deals and selling cars when he was still in school," and then moved on to establish a pharmaceutical company, and to being involved in "development projects that could involve millions of dollars, arranging deals for oil exploration, electric generating, housing projects and the like."

Al-Hela was also working with the Yemeni government when he was kidnapped in Cairo on a business trip in September 2002, and "rendered" to a notorious CIA “black site” in Afghanistan, the "Dark Prison", a medieval torture facility with the addition of permanent, screaming loud music. Subsequently moved around other secret prisons in Afghanistan — run by Afghans on behalf of the U.S. — he eventually ended up at Bagram until, after two years in total in secretive and abusive prisons in Afghanistan, he was finally flown to Guantánamo.

At Guantánamo, the story eventually emerged that the U.S. authorities suspected that, in his work with the Yemeni government and its intelligence service, the Political Security Organization, he had been involved with Al-Qaeda. His job, as a colonel in intelligence, involved, as a Human Rights Watch report in 2005 explained, being in charge of the "Arab Afghan file," dealing with the "hundreds and possibly a thousand or more" former mujahideen who had fought against the Russians in Afghanistan, as well as "an estimated 30,000 Yemenis" who had also subsequently traveled to Afghanistan.

This job involved him "transferring scores of Arab Islamists from Yemen to other countries, including Western Europe, to seek asylum," and meant that "he had a close relationship with Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh, as well as with a broad array with Arab and Western intelligence services, and members of the militant groups themselves." Somewhere along the line, however, a rumor arose that he was involved with moving some these individuals around the world on behalf of Al-Qaeda, even though, as Human Rights Watch explained, individuals "familiar with the Islamist scene in Yemen" said that it was actually "his knowledge of the Islamists’ exodus out of his country" that "made him a valuable source of information for the CIA."

This has always struck me as the most plausible reason for his abduction, which took place during a particular period, in 2002 and 2003, when, as I described it in 2016, "the CIA seemed to be giddy with power, abducting people and rendering them to be tortured on the shallowest of bases."

Certainly, there is nothing to suggest that the U.S. authorities had a viable case against al-Hela. Throughout the rest of his time at Guantánamo under George W. Bush, he was never charged in the military commissions, and nor was he put forward for trial when, in 2009, the first year of Obama’s presidency, the first of Obama’s two review processes, the Guantánamo Review Task Force, assessed the cases of the 240 men inherited from Bush, concluding that 156 should be freed and 36 prosecuted, while 48 others should continue to be held indefinitely without charge or trial.

Al-Hela was put into this latter category, "subject to further review," which eventually came about in 2016, three years after Obama had established his second review process, the Periodic Review Boards (PRBs), a parole-type system that involved prisoners being given an opportunity to persuade board members that it was safe to release them.

Al-Hela’s first PRB took place in May 2016, but despite positive contributions by his personal representatives (military personnel assigned to represent him) and by his civilian lawyer David Remes, the board members approved his ongoing imprisonment the month after.

Under Trump, the PRBs were largely boycotted by the prisoners, who concluded that they had become a sham. Al-Hela had his case reviewed again in June 2018, and again had his ongoing imprisonment upheld the month after, and it wasn’t until Joe Biden took office that the allegations against him — which, as I described it at the time, had "ossified into an apparently unshakeable belief that he 'was a prominent extremist facilitator who used his position within the Yemeni Political Security Organization to provide refuge and logistical support to al-Qa’ida and other extremist groups'" — were finally put aside in favor of a decision to approve him for release.

As I also explained at the time, the contributions of his lawyer, Beth Jacob, had undoubtedly helped. Throughout the long years of his imprisonment, he had lost his two young sons in a tragic accident, and had also lost his mother and one of his brothers, and, as Jacob described it, he wanted only "to devote himself to his family to make up for the long years away from his wife and daughter."

Jacob also included letters from prominent Yemeni officials explaining that he was acting for the government, and that he did not have "any connection with any terrorist or extremist organizations," and, after reviewing the successful upward trajectory of his life before his abduction, she dared to conclude by pointing out that "[t]he accusations against him make no sense."

1,000 days since al-Hela was approved for release, it is surely beyond time that his only wish — to be reunited with his family — is finally granted.

A poster showing how long the 16 men approved for release from Guantánamo have been held since the U.S. authorities approved their release, as of March 6, 2024.

The story of Sharqawi al-Hajj

Sharqawi al-Hajj (ISN 1457), a Yemeni who is 49 years old, was seized in a house raid in Karachi, Pakistan on February 7, 2002, on the same day that 15 other men were also seized in at least two other raids. These men were all transferred to Guantánamo, but al-Hajj was, instead, chosen for torture. Because the CIA had not yet established its first "black site," however, which opened in Thailand immediately after the capture of Abu Zubaydah, on March 28, 2002, he was, instead, after a week or so in U.S. custody, sent to Jordan, where the Jordanian government’s notorious torturers, in the General Intelligence Directorate (GID), were, obligingly, also torturing prisoners "rendered" to them by the U.S.

Al-Hajj was held and tortured in Jordan for nearly two years, and he described his ordeal in a hand-written note, written in October 2002, which was smuggled out of the prison and given to Joanne Mariner of Human Rights Watch in 2008. In the note, he stated, "They beat me up in a way that does not know mercy, and they're still beating me. They threatened me with electricity, with snakes and dogs. [They said] we'll make you see death."

In the note, al-Hajj also explained how, as Mariner described it, "the Jordanians were feeding his responses back to the CIA." As he stated, "Every time that the interrogator asks me about a certain piece of information, and I talk, he asks me if I told this to the Americans. And if I say no he jumps for joy, and he leaves me and goes to report it to his superiors, and they rejoice."

In a later account, included in "Double Jeopardy: CIA Renditions to Jordan," Human Rights Watch’s important 2008 report about the outsourcing of torture to Jordan, al-Hajj explained how, as I described it, "prisoners were shown photo albums prepared by U.S. interrogators — generally known as 'the family album' — and pressurized to identify the men in the photos and to make statements about them, whether they knew them or not." As al-Hajj said, "I was being interrogated all the time, in the evening and in the day. I was shown thousands of photos, and I really mean thousands, I am not exaggerating," a comment which, I have always believed, reveals the extent to which false confessions were established through the use of torture, contaminating so much of what the U.S. government subsequently tried to claim as reliable evidence.

In January 2004, al-Hajj was flown to the "Dark Prison" in Kabul, where he was held for four months, and which he described as "a pitch dark place, with extremely loud scary sounds," and was then held for another four months in Bagram, before his eventual transfer to Guantánamo.

Despite being regarded by the U.S. authorities as a "senior facilitator" for Al-Qaeda, known as "Riyadh the Facilitator," al-Hajj was not put forward for a trial by military commission under the Bush administration, and although Obama’s Guantánamo Review Task Force recommended him for prosecution in its final report in January 2010, he was never charged under Obama either.

Instead, his torture surfaced in 2010 in the habeas corpus case of a fellow prisoner, Uthman Abd Al-Rahim Mohammed Uthman, when District Judge Henry H. Kennedy Jr. excluded statements he and another prisoner had made, which the Justice Department had sought to submit as evidence, because, as he stated, "there is unrebutted evidence in the record that, at the time of the interrogations at which they made the statements, both men had recently been tortured." Judge Kennedy explicitly cited al-Hajj’s treatment in Jordan and Kabul, noting that he had specifically told his attorney, Kristin B. Wilhelm, that, in Jordan, "he eventually 'manufactured facts' and confessed to his interrogators’ allegations 'in order to make the torture stop.'"

In 2011, during deliberations regarding al-Hajj’s own habeas corpus petition (which, incidentally, never reached a final decision), Chief Judge Royce Lamberth also found that al-Hajj had been tortured, noting that "the Court finds that respondents [the Justice Department] — who neither admit nor deny petitioner’s allegations regarding his custody in Jordan and Kabul — effectively admit those allegations. Accordingly, the Court accepts petitioner’s allegations as true."

Another of his attorneys, John A. Chandler, responded by stating that, "After years of torture, an FBI clean team came in to start interrogations anew in the hope of obtaining information that was admissible and not the product of torture," a rare and illuminating reference to the fact that, having recognized that statements made under torture would be inadmissible, the U.S. government had sought to secure new and allegedly untainted evidence by getting al-Hajj to repeat confessions he had previously made under torture to FBI agents who, after his arrival at Guantánamo, interrogated him non-coercively.

Last summer, long-standing efforts by the government to use supposed "clean team" evidence in the case of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, the alleged mastermind of the USS Cole bombing in 2000, collapsed when his trial judge memorably refused to accept their legitimacy.

In al-Hajj’s case, however, the largely unknown efforts to also prosecute him using "clean team" evidence collapsed back in 2011, when, as Chandler noted, "The Courts … held that torture after Karachi excludes all his interrogations."

As Chandler added, poignantly, "Nearly 10 years [after his capture], Sharqawi sits in Guantánamo. His health is ruined by his treatment by or on behalf of our country. He can eat little but yogurt. He weighs perhaps 120 pounds. The United States of America has lost its way."

It took until 2013 for the Obama administration to finally abandon efforts to prosecute al-Hajj, transferring him instead into the Periodic Review Board process. In March 2016, his first PRB took place, but he failed to attend, and, as a result, it was unsurprising that the board members approved his ongoing imprisonment. Another PRB in 2017 also upheld his ongoing imprisonment, around the same time that his lawyers, at the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights, filed an emergency motion asking for a judge to order an independent medical examination for him, and to allow the release of his medical records.

As a long-standing hunger striker, al-Hajj’s weight had plummeted to just 104 pounds, and, in a medical declaration accompanying the emergency motion, Dr. Jess Ghannam, a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, assessed that he could be on the verge of "total bodily collapse."

Shamefully, al-Hajj’s emergency motion was never dealt with, and his physical frailty was compounded, in 2018, with the emergence of severe mental health problems when, as his lawyers explained in a profile of ten prisoners published last year, "he began making desperate statements to his counsel about wanting to hurt himself and having no hope."

In August 2019, as CCR explained in a subsequent press release, he "cut his wrists with a piece of glass while on a recent call with his lawyer, after making specific statements in prior weeks about wanting to 'try to kill himself.'" He stated that he was "sorry for doing this but they treat us like animals," and added, "I am not human in their eyes."

In March 2020, he harmed himself again, and, given the U.S. authorities’ shameful refusal to provide adequate physical and mental health care to the men still held at Guantánamo, and their similarly shameful refusal to provide rehabilitation for victims of the CIA’s torture program — as highlighted in a damning report issued last year by Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism, after the first ever visit to the prison by a U.N. Rapporteur — it appears to be nothing short of a minor miracle that he was still alive when, on June 8, 2021, he was finally approved for release by a Periodic Review Board.

At his hearing, in April 2021, his attorney, Pardiss Kebriaei, urged the Board members to consider a statement al-Hajj made in 2017, which, as she said, still "holds true." As she described it, "As he stated then, he is not the same person he was in his 20s, and has no interest in behavior that may result in more deprivation. He wants to be away from violence and negative influences, and is convinced that fighting and wars are futile."

Although the U.S. authorities persisted in describing al-Hajj as an Al-Qaeda "facilitator," they clearly recognized, by this point, that previous claims about his significance had been exaggerated, conceding that he "may not have had foreknowledge" of any terrorist attacks or plots, and accepting that he "does not currently demonstrate an extremist mindset or appear to be driven to reengage by extremist ideology."

As with all of the men approved for release but still held, however, words are not enough, and action is needed to ensure that both Abdulsalam al-Hela and Sharqawi al-Hajj are freed. In al-Hajj’s case, as CCR recognizes, he will particularly need the medical and psychological support that has been so disgracefully denied him at Guantánamo, although he has family members who are more than willing to help. Although his parents both died in recent years, he has siblings who have all assured the U.S. government of "their ability and willingness to offer emotional and financial support" to him after his release.

Further delays are unconscionable, and President Biden should secure the release of these men as swiftly as possible.

NOTE: For a Spanish version, on the World Can't Wait's Spanish website, see "Detenidos durante 1.000 días desde que se aprobó su excarcelación de Guantánamo: Abdulsalam Al-Hela y Sharqawi Al-Hajj."