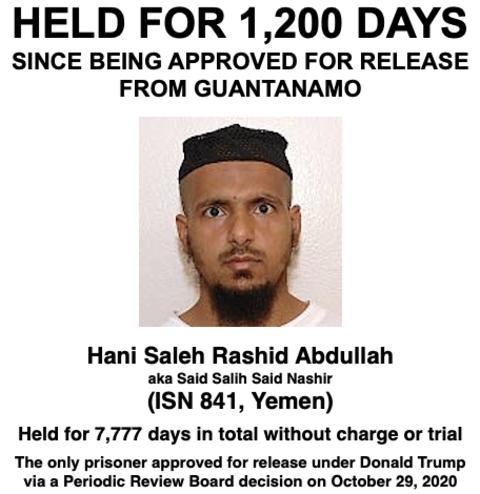

Held for 1,200 Days Since Being Approved for Release from Guantánamo: Hani Saleh Rashid Abdullah

Hani Saleh Rashid Abdullah, and the graphic we have made showing how long he has been held since the U.S. authorities decided that they no longer wanted to hold him.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout 2024. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, February 12, 2024

This is the second of a new series of profiles of men held at Guantánamo — specifically, the 16 men (out of the 30 still held) who have long been approved for release by high-level U.S. government review processes. The first profile was published on February 7 on my website, and further profiles will be published throughout February and March — alternating between my website and here.

Today I’m focusing on Hani Saleh Rashid Abdullah, also identified by the U.S. authorities as Said Salih Said Nashir, a 48- or 49-year old Yemeni citizen, who, as of yesterday (February 11), had been held for 1,200 days since the U.S. authorities decided that they no longer wanted to hold him.

Hani arrived at Guantánamo on October 28, 2002. The photo is from his classified military file, released by WikiLeaks in April 2011, and dating from June 2008, meaning that he would have been 33 or 34 years old, or younger, when it was taken.

Since his arrival at Guantánamo — 7,777 days ago (that’s 21 years and 107 days) — Hani has been held without charge or trial, and with no sign of when, if ever, he will eventually be freed, even though the high-level government review process that approved him for release concluded unanimously, on October 29, 2020, that "continued law of war detention is no longer necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States."

The review process, known as the Periodic Review Boards (PRBs), is a parole-type process initiated by President Obama, "comprised of senior officials from the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Justice, and State; the Joint Staff; and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence," as its website explains.

Unfortunately, Hani is still held because the PRBs are a purely administrative process, and carry no legal weight, meaning that there is no one Hani can appeal to — a federal court judge, for example — if, as is apparent from how long he has been held since the decision to approve him for release was taken, the Biden administration shows no interest in actually freeing him.

To be fair to the U.S. government, there is a complication. Most, if not all of these 16 men cannot be repatriated, because of provisions inserted every year by Republicans into the National Defense Authorization ACT (NDAA), preventing their return to their home countries — Yemen, in most cases, but also Somalia and Libya.

As a result, third countries must be found that are prepared to offer new homes to these men. However, although President Biden belatedly appointed an official in the State Department — former ambassador Tina Kaidanow — to oversee resettlement issues relating to Guantánamo in the summer of 2021, the resettlement of these men is clearly not being prioritized by those in the chain of command above her; very specifically, President Biden himself, and Antony Blinken, the Secretary of State.

What makes the case of these 16 men even more shameful is that, last year, when the Biden administration was legally obliged to release Majid Khan, a remorseful Al-Qaeda courier who had been charged in the military commissions at Guantánamo, and had agreed to a plea deal whereby, in exchange for his cooperation with ongoing trials at Guantánamo, he would be freed, the U.S. government — at, presumably, the highest level — successfully negotiated his resettlement in Belize, whereas 16 men never even charged with a crime cannot get out of Guantánamo at all because there is no legal obligation for them to be freed.

Not for the first time at Guantánamo, those treated most dismissively — and apparently consigned to lifelong imprisonment without charge or trial — are those who are too insignificant to even be charged with a crime.

Through this series of profiles, we hope to raise the profile of these 16 men, who, as of yesterday, had been held for between 506 and 1,200 days since they were approved for release — and in three cases for a truly shocking 5,133 days — to help to push the Biden administration into recognizing that its failure to release these men is completely unacceptable.

Hani’s story

Hani is one of six Yemenis seized in a house raid in Karachi, Pakistan on September 11, 2002, the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, in one of three house raids that took place on that day. Four other individuals were seized in the other two house raids, one securing the capture of alleged 9/11 co-conspirator Ramzi bin al-Shibh and Hassan bin Attash, who was just 17 years old at the time, and is the younger brother of another alleged 9/11 co-conspirator, Walid bin Attash, while the other led to the capture of the Rabbani brothers, Ahmed and Abd al-Rahim, who were freed last year.

These ten individuals were all sent to be tortured in CIA "black sites," and all eventually resurfaced at Guantánamo — bin al-Shibh in September 2006, and bin Attash and the Rabbanis in September 2004. Hani and the five men seized with him were, however, only held for six weeks in "black sites" before their transfer to Guantánamo in October 2002, indicating that, from the beginning, the U.S. authorities were aware that they were fundamentally insignificant.

Nevertheless, on arrival at Guantánamo they were labeled as the "Karachi Six," nebulously regarded as recruits for some future terrorist attack, even though, objectively, there was no reason to presume that they were anything more than foot soldiers for the Taliban, who had ended up in Karachi after fleeing Afghanistan and being shunted around Pakistan as they sought to return home.

Like the majority of the Guantánamo prisoners (except for the few who were actually charged with crimes), these six men were held without charge or trial for the next six years, their cases only reviewed by cursory administrative review processes (the Combatant Status Review Tribunals and Administrative Review Boards), which found that they had, on capture, been correctly designated as "enemy combatants," who could be held indefinitely without charge or trial.

This appallingly lawless scenario only came to an end in June 2008, when, in Boumediene v. Bush, the Supreme Court ruled that all the Guantánamo prisoners had constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights. For the next two years — until politically motivated appeals court judges rewrote the habeas rules, effectively gutting habeas of all meaning for the Guantánamo prisoners — judges ordered the release of over 30 prisoners, after ruling that the government had failed to establish that they had any meaningful connection to Al-Qaeda or the Taliban.

For the "Karachi Six," however, the only one to have his habeas petition considered — Musa’ab al-Madhwani — had it turned down in December 2009, when the judge in question, District Judge Thomas F. Hogan, found that, although he was a "model prisoner," he had "trained, traveled, and associated with members of al-Qaida, including high-level operatives," and that, therefore, he was "lawfully being detained under the AUMF," the Authorization for Use of Military Force, passed by Congress the week after the 9/11 attacks, which authorized the president to detain those regarded as having connections to Al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

It then took another six years for there to be any movement in the cases of these six men. When President Obama took office in January 2009, he convened a high-level review process, the Guantánamo Review Task Force, which, for a year, deliberated on the cases of the 240 prisoners inherited from George W. Bush, and, in January 2010, concluded that 156 should be freed, 36 should be prosecuted, and 48 should continue to be held indefinitely without charge or trial.

The "Karachi Six" were assigned to this latter category, and when President Obama, recognizing that reviews of these men’s status would be required to fend off allegations of arbitrary imprisonment, established another review process, the Periodic Review Boards (PRBs), to review the basis of their imprisonment on a parole-type basis, the six men were included.

The Periodic Review Boards

The PRBs didn’t begin until November 2013, and it took until February 2016 for the first of the "Karachi Six," Ayub Murshid Ali Salih, to have his case considered, when, finally, the government conceded that, as I reported at the time, "although the six Yemenis were initially 'labeled as the "Karachi Six," based on concerns that they were part of an al Qa’ida operational cell intended to support a future attack,' it had become apparent that 'a review of all available reporting' indicated that 'this label more accurately reflects the common circumstances of their arrest and that it is more likely the six Yemenis were elements of a large pool of Yemeni fighters that senior al-Qa’ida planners considered potentially available to support future operations.'"

In the months that followed, four other members of the non-existent "Karachi Six" cell were also recommended for release, and, as I later explained, these five men "were subsequently released, although they all had to be resettled in third countries, because of a long-standing prohibition against repatriating Yemeni prisoners, based on the security situation in their home country. One of the five was sent to Cape Verde, two others were sent to Oman, and the other two, unfortunately, were sent to the United Arab Emirates, where, instead of the freedom they were promised, they [were] subjected instead to ongoing imprisonment and abuse in secret prisons," until they were forcibly repatriated to Yemen in 2021.

Inexplicably, however, Hani’s ongoing imprisonment was upheld in November 2016, six months after his PRB, and although a follow-up hearing was swiftly scheduled, in December 2016, the board reached the same decision in January 2017, and he then had to wait until November 2019 for another opportunity to persuade the board that he didn’t pose a threat to the U.S.

This time it took the board members eleven months to reach a decision in his case, but finally, on October 29, 2020, the board approved him for release, albeit subject to "robust security assurances to include monitoring, travel restrictions and integration support, as agreed to by relevant USG departments and agencies."

As I explained at the time, at his hearing in November 2019, "his attorney, Charley Carpenter, who has represented [him] since 2005, reminded the board that Hani, as he knows him, 'is a relatively simple, perhaps naive, man, not given to artifice or scheming,' who finds the hearings 'highly stressful,' and sought to address concerns the board had raised in 2016 about his client’s past activities, which he had clearly spent some time investigating."

I added, "His contributions, and that of his fellow attorney, Steve Truitt, evidently helped to persuade the board to approve Hani’s release, with the board members stating in their decision that they had 'considered [his] low level of training and lack of leadership position in Al Qaeda or the Taliban, [his] candor regarding his activities in Afghanistan and with Al Qaeda, and [his] efforts to improve himself while in detention, to including taking numerous courses at Guantánamo.' They also noted 'the ability and willingness of [his] family to support him in the event of a transfer, [his] credible plan for supporting himself in the event of a transfer, and significant improvement in [his] compliance since his last hearing in 2016.'"

Speaking to NPR after the decision was made public, Charley Carpenter called it "recognition, as we’ve always thought, that continued imprisonment of this man doesn’t help the national security of the United States."

He added that securing the recommendation for release had been "a long odyssey," adding, presciently, that "it isn’t over yet," although it "means that a significant hurdle in his effort to go home has been cleared." As he added, he was "optimistic that the incoming administration will renew efforts to move people out of the prison [at] Guantánamo."

1,200 days later, Charley Carpenter’s caution was clearly justified, but as we recall this sad occasion, and reflect on the 7,777 days that Hani has been held in total, without charge or trial, it is surely time for the Biden administration to put some effort into giving him the freedom he so thoroughly deserves.

When I emailed Hani’s attorneys to ask them how he was coping, Steve Truitt replied, "At the end of the day Hani does not rely on U.S. lawyers for his release. He trusts in Allah. I think this keeps him sane."

That is commendable, of course, but it does nothing to reduce the shame that ought to be felt by the Biden administration as its disregard for basic decency is so openly displayed.

NOTE: For a Spanish version, on the World Can't Wait's Spanish website, see "Hani Saleh Rashid Abdullah lleva 1.200 días detenido desde que se aprobó su excarcelación de Guantánamo."