18 Years After 9/11, the Endless Injustice of Guantánamo is Driving Prisoners to Suicidal Despair

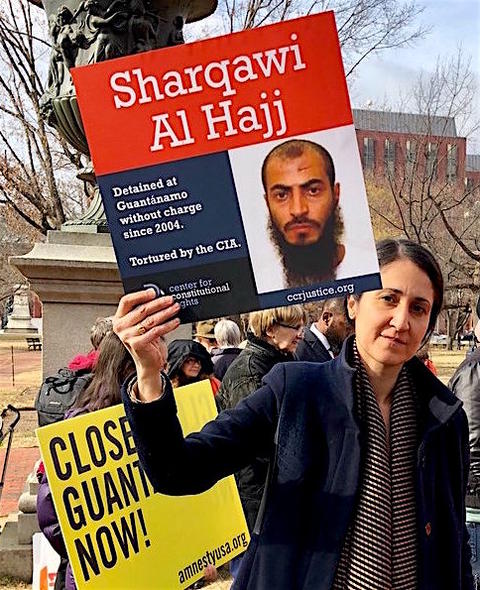

Pardiss Kebriaei, Senior Staff Attorney with the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights, holds up a placard outside the White House on January 11, 2018, the 16th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, featuring "forever prisoner" Sharqawi Al Hajj, who made a suicide attempt at the prison last month (Photo: Shelby Sullivan-Bennis).

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout the rest of 2019. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, September 10, 2019

18 years ago, on September 11, 2001, the world changed irrevocably, when terrorists, using hijacked passenger planes, attacked the U.S. mainland, killing nearly 3,000 people. In response, the administration of George W. Bush launched a brutal, global "war on terror," invading Afghanistan to destroy Al-Qaeda and to topple the Taliban government, and embarking on a program of kidnapping ("extraordinary rendition"), torture and the indefinite detention without charge or trial of alleged "terror suspects."

18 years later, the war in AfghanIstan drags on, the battle for "hearts and minds" having long been lost, a second occupied country — Iraq — illegally invaded on the basis of lies, and of false evidence obtained through torture, remains broken, having subsequently served as an incubator for Al-Qaeda’s savage offshoot, Daesh (or Islamic State), and the program of indefinite detention without charge or trial continues in the prison established four months after the 9/11 attacks, at Guantánamo Bay on the U.S. naval base in Cuba.

Torture, we are told, is no longer U.S. policy and the CIA no longer runs "black sites" — although torture remains permissible in Appendix M of the Army Field Manual, and no one can quite be sure what the U.S. gets up to in its many covert actions around the world.

What is clear, however, is that torture continues to permeate Guantánamo, corroding efforts to bring the alleged 9/11 perpetrators to justice, because the government is still trying not to publicly admit to what it did to the men in their long years in the "black sites" — despite it being exposed so thoroughly in the executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report into the CIA’s torture program, which was released in December 2014 — while the men’s defense teams, of course, point out that there can be no justice unless the truth is exposed.

For those not facing trials — 31 of the 40 men still held — there no longer appears to be any attempt by the authorities to even pretend that they should receive any form of justice. Under George W. Bush, most of the men released were freed because of political pressure from their home countries. From 2008 to 2010, there was a brief period when, following a momentous Supreme Court ruling, the law penetrated Guantánamo, and 38 men had their habeas corpus petitions granted by U.S. judges, until appeals court judges cynically rewrote the rules, gutting habeas corpus of all meaning — and vacating or reversing five of those decisions.

To his credit, Barack Obama initiated two review processes to deal with the prisoners he inherited from George W. Bush. The first, 2009’s Guantánamo Review Task Force, approved 156 prisoners for release (roughly two-thirds of those held when he took office), and all but three of those men were eventually released. And from 2013-16, the Periodic Review Boards (PRBs), a parole-type process, partly designed to sidestep Republican efforts to prevent any releases from the prison, led to another 38 men being approved for release, with all but two of them released before Obama left office.

However, 26 men had their ongoing imprisonment approved by the PRBs, and, with the five men approved for release but still held, these 31 men are locked in Guantánamo, apparently forever, by Donald Trump, who, even before he took office, announced that there should be no further releases from Guantánamo.

The PRBs continue, but have not delivered a single recommendation for release since Trump took office, and the prisoners, as a result, are sinking into a grave sense of despair. Human Rights First, the only organization to consistently keep an eye on the PRBs, has regularly been reporting that prisoners are no longer attending their hearings, having concluded that, under Trump, they have become a sham.

For a roll-call of prisoners refusing to engage with the PRBs, see their articles, Alleged Bin Laden Bodyguard Boycotts Periodic Review Board Process (in December 2018), No End in Sight for GTMO Detainee and Another GTMO Detainee Refuses to Participate in PRBs (in February this year), Another GTMO Detainee Opts Out of the Review Process (in April), Two PRB Reviews and Two No-Shows as Detainees Continue to Opt Out (in May), Another Detainee No-Show Demonstrates a Defunct PRB Process (in June) and PRB Hearings Continue While Guantanamo Detainees Sit on the Sidelines (in August).

A suicide attempt by Sharqawi Al Hajj

Last week in a shocking demonstration of how deep the despair at Guantánamo runs, the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) issued a press release in which they revealed that their client Sharqawi Al Hajj recently attempted suicide.

In an emergency motion submitted to the District Court in Washington, D.C., CCR revealed that Al Hajj had "cut his wrists with a piece of glass while on a recent call with his lawyer [on August 19], after making specific statements in prior weeks about wanting to 'try to kill himself,'" which I reported in an article last week.

In the motion, CCR’s attorneys state that there "appeared to be utter confusion for several minutes about what was going on," with Al Hajj stating that he was "sorry for doing this but they treat us like animals," and adding, "I am not human in their eyes."

Al Hajj also told his attorneys that he “had been moved to a Behavioral Health Unit in Guantánamo after his [previous] suicidal statements, where he was held in harsh, isolating conditions, despite being told by his doctor that the doctor had recommended against the move. In the unit, [he] began protesting by refusing to drink water for two days. By the third day he was urinating blood and was in the hospital. After his discharge, [he] was placed in a cell that felt freezing cold to [him] because of his frail condition, and was denied doctors’ recommendations for a warm blanket and warm clothes. In protest, he stopped drinking water again."

On Friday Al Hajj’s attorneys urged the court to order "an immediate independent psychiatric assessment of Mr. Al Hajj to prevent further harm or death."

CCR Senior Staff Attorney Pardiss Kebriaei said, "Any notion that Mr. Al Hajj is not actively suicidal is deliberately blind or indifferent. For months he has made increasingly hopeless and suicidal statements of intent and planning, culminating in an actual premeditated attempt, in a context where the outlook couldn’t be bleaker – no prospect of release after more than 17 years of captivity."

She added, "When similar behavior by Guantánamo detainees in the past has not been taken seriously, detainees have died. Mr. Al Hajj’s actions must be treated with the utmost gravity and care by everyone with responsibility over him."

As CCR also explained, "Attorneys began raising alarms about Mr. Al Hajj two years ago, after he fell unconscious following a hunger strike during which he stopped drinking water. At the time, medical experts warned the court that Mr. Al Hajj was in danger of 'imminent irreparable harm' and 'on the precipice of total bodily collapse.' They cited both pre-existing health conditions as well as the effects of Mr. Al Hajj’s indefinite detention — now at over 17 years — including over two years of torture in secret CIA custody."

In response to his deteriorating condition, CCR filed an emergency motion two years ago, in September 2017, calling for the release of his medical records and an evaluation by an independent doctor, which I wrote about at the time. Astonishingly, however, the court has not yet ruled on that motion.

Since then, as CCR proceeded to explain, "Mr. Al Hajj’s mental and physical health have been in steady decline." Last October, his attorneys filed an urgent request to appear before the court, because of concerns about his mental health, but the courts have, fundamentally, let him down.

It remains to be seen if the courts will finally address the contempt for any notion of justice that emanates from the White House and from Congress when it comes to Guantánamo, although, to date, the wheels of justice appear to be moving at a glacial pace.

Sharqawi Al Hajj is one of 11 prisoners who submitted a habeas corpus petition to the District Court in Washington, D.C. in January 2018, when their lawyers declared that, "Given President Donald Trump’s proclamation against releasing any petitioners — driven by executive hubris and raw animus rather than by reason or deliberative national security concerns — these petitioners may never leave Guantánamo alive, absent judicial intervention."

In this case, however, as with Sharqawi Al Hajj’s emergency motion of September 2017, no ruling has yet been delivered, and while the delays continue, it seems, from Al-Hajj’s despair, that the prisoners’ very lives are at stake.

POSTSCRIPT: As this article was being published, the judge "refused to order an independent medical evaluation of Sharqawi Al Hajj," as CCR explained in a press release. Pardiss Kebriaei. said, "In the face of Guantánamo’s inability to change the course of Mr. Al Hajj’s mental health trajectory from suicidal statements to actual attempt, and independent medical opinion that Mr. Al Hajj is 'actively suicidal,' the court’s denial of an outside medical evaluation takes a chance with Mr. Al Hajj’s life. Mr. Al Hajj’s attempt was not taken seriously, and it was seen as volitional – harm of his own making, as if he weren’t a prisoner we had tortured and imprisoned without charge for 17 years, with still no prospect of release, and as if willfulness matters in the assessment of real risk."