President Elect Biden, It’s Time to Close Guantánamo

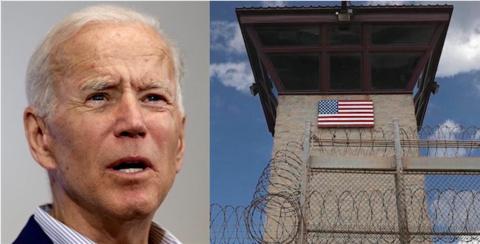

A composite image of Joe Biden and the prison at Guantánamo Bay.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout the rest of 2020. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, November 12, 2020

Congratulations to President Elect Joe Biden and Vice President Elect Kamala Harris for persuading enough people to vote Democrat to end the dangerous presidency of Donald Trump.

Trump was a nightmare on so many fronts, and had been particularly dangerous on race, with his vile Muslim travel ban at the start of his presidency, nearly four long years ago, his prisons for children on the Mexican border, and, this last year, in his efforts to inflame a race war, after the murder of George Floyd by a policeman sparked huge protests across the country.

At Guantánamo, Trump’s racism manifested itself via indifference to the fate of the 40 Muslim men, mostly imprisoned without charge or trial and held for up to 15 years when he took office. To him they were terrorists, and he had no interest in knowing that very few of the men held at Guantánamo have ever been accused of involvement with terrorism, and that, of the 40 men still held, only nine of them have been charged with crimes, and five of them were unanimously approved for release by high-level government review processes under President Obama.

Trump also wasn’t interested in the rest of the men — 26 in total — who were without status, "forever prisoners" still held because Obama’s reviews found that they still constituted some sort of a threat to the United States.

Instead, he tweeted that "there must be no more releases from Gitmo" even before he took office, and remained true to his word with the one exception of Ahmed al-Darbi, a Saudi sent back to Saudi Arabia in 2018, to ongoing imprisonment, as part of a plea deal in his military commission trial, conducted in 2014 when Obama was still president.

Entombed by Donald Trump

After the last four years, in which the remaining prisoners have, essentially, been entombed by Donald Trump in a limbo without end, it is time that as many as possible of these 40 men are released — not just the five men approved for release under Obama, but many, if not most of the other 26.

For some of these men, the rationale for holding them has always been inadequate. Foot soldiers for the Taliban in the inter-Muslim civil war that preceded the 9/11 attacks and the U.S.-led invasion, they are only regarded as constituting a threat because of their attitude while imprisoned. In some cases this is because they have been hunger strikers, resisting the injustice of their long imprisonment without charge or trial in the only way left to those rendered powerless by their captors, while others have, ironically, been singled out as threats because of their charisma or their compassion — men who have become cell block leaders, or spiritual leaders, having shown an ability to care for their fellow prisoners. In some cases, the men still held appear to be cases of mistaken identity.

We have focused on the stories of many of the men over the years: the men approved for release, like Abdul Latif Nasser, who missed being released by just eight days, and Sufyian Barhoumi, an Algerian. Both men were approved for release in 2016, Obama’s last year in office, by Periodic Review Boards, but were the only two men out of 38 in total not to be released before Obama left office. The other three were approved for release ten years ago, after the deliberations of Obama’s first review process, the Guantánamo Review Task Force, and are the only three out of 156 men recommended for release by the task force who were not released. One, Tawfiq al-Bihani (spelled "Toffiq" by the U.S. authorities) once thought he was getting on a plane to leave Guantánamo, but it never happened. Little is known of the two others.

As well as releasing these men, the Biden administration should look closely at who it is holding amongst the "forever prisoners" — like Saifullah Paracha, Guantánamo’s oldest prisoner, a Pakistani businessman and model prisoner, who is widely respected by his fellow prisoners and by the prison’s military personnel, as his friend Mansoor Adayfi, now living in Serbia, explained in an article for us in October 2018, entitled, Saifullah Paracha: The Kind Father, Brother, and Friend for All at Guantánamo.

Another prisoner well-respected by his fellow prisoners and by prison staff is Khaled Qassim, a Yemeni — one of several "forever prisoners" to have had his artwork seen by the outside world. I wrote about Khalid’s artwork in February this year, in an article entitled, Humanizing the Silenced and Maligned: Guantánamo Prisoner Art at CUNY Law School in New York, after visiting an exhibition of artwork by prisoners past and present, and Mansoor Adayfi has also written poignantly about him in an article entitled My Best Friend and Brother, noting his relentless concern for others.

Qassim is not the only artist among the "forever prisoners," for whom ongoing imprisonment seems absurd. Muaz al-Alwi (spelled "Moath" by the U.S. authorities) makes astonishing ships out of recycled materials — or did. I have no clear way of knowing if he is still allowed to make them, after the first exhibition of prisoners’ art was held in New York in 2017, and the Pentagon responded by clamping down on the prisoners’ freedom of expression.

Then there are the cases of mistaken identity, or exaggerated significance: for example, Asadullah Haroon Gul, an insignificant Afghan, Muhammad Rahim, the other remaining Afghan, who is vouched for by high-ranking Afghans, Ahmed Rabbani, a taxi driver from Pakistan mistakenly identified as another prisoner who U.S. forces picked up independently, and Omar al-Rammah, a Yemeni seized in Georgia in 2002, who has had no contact at all with his famlly.

Another prisoner whose case has been in the news this year is Mohammed al-Qahtani, tortured at Guantánamo in 2002, but who had profound mental health problems even before his torture. Al-Qahtani recently had a court grant his lawyers’ request for an objective analysis of the state of his mental health, in the hope of it leading to a recommendation that he should be repatriated because the authorities at Guantánamo are incapable of addressing his needs. It is not known how many other prisoners have serious mental health issues, but hints that other prisoners also have long-standing mental health issues have surfaced over the years.

For others — those held and tortured in CIA "black sites" — their torture is incompatible with justice. This is known but largely unacknowledged within the U.S. government, because, over 14 years since the military commission trial system began, it still staggers on, but with trial dates endlessly deferred. Over these 14 long years, the commissions have only ever secured a handful of convictions, mostly via plea deals, and many of those have been overturned on appeal.

Eventually, the U.S. is going to have to acknowledge that it must either charge prisoners and put them on trial in a functional system (i.e. federal courts, not the military commissions), or release them, and we believe that the fourth president to take control of Guantánamo needs to be the one to bring to an end the enduring shame of a prison that makes a mockery of the U.S.’s claimed respect for the rule of law every day that it remains open. Only dictatorships hold people indefinitely without charge or trial.

The way forward

Detailed proposals for how the Baden-Harris transition team should deal with Guantánamo have already been put forward by a number of NGOs and human rights groups, as posted on the Just Security website, and cross-posted here as A Roadmap for the Closure of Guantánamo.

On Day One — along with executive orders already mentioned by the transition team, including dropping the Muslim ban, re-committing the U.S. to the Paris climate accords, and reinstating its commitment to the World Health Organization, both of which were dropped by Trump — it would be heartening to see Joe Biden also issuing an executive order that repudiates Trump’s executive order keeping Guantánamo open, which he issued in his first few weeks in office.

Biden should also immediately kick-start arrangements for the release of the men already approved for release, by reinstating the Office of the Envoy for Guantánamo Closure, a role that not only involved arranging for the resettlement of former prisoners, but also monitored them, both to ensure that were not subjected to ill-treatment, and also from the point of view of national security.

Under Trump, the US abdicated all responsibility for former prisoners, with no one at all in a position of responsibility when two Libyans resettled in Senegal were recklessly repatriated in 2018, promptly disappearing into lawless, militia-run prisons, and no one to liaise with the United Arab Emirates regarding the fate of nearly two dozen men resettled there in Obama’s last 14 months in office, who were promised the opportunity to rebuild their lives, but who, for the most part, have continued to be imprisoned, often, it seems, in abusive conditions.

As you read this, the UAE is threatening to repatriate 18 Yemeni citizens who made up the bulk of the ex-prisoners, which is not only perilous for them, given the ongoing Western- and Saudi-backed civil war in Yemen, but also flies in the face of the U.S.’s long-established position regarding Yemeni prisoners held at Guantánamo, which, for the most part, under Bush and Obama, involved a refusal, across the whole of the U.S. political establishment, to even contemplate the repatriation of Yemeni prisoners.

Biden also needs to do more than just reinstate the envoy role: as the NGOs and human rights groups explained, he also needs to appoint "a senior director of a reconstituted multilateral affairs and human rights directorate, or its equivalent, at the National Security Council," to oversee the process of working towards the closure of Guantánamo.

We hope Joe Biden is listening. We know Guantánamo is almost invisible now, and far too few people care about it, but we remain sure that a Biden administration will recognize that something that is fundamentally wrong cannot be ignored just because it has largely been forgotten — and especially with the 20th anniversary of its opening just over a year away.