Humanizing the Silenced and Maligned: Guantánamo Prisoner Art at CUNY Law School in New York

Artwork by Guantánamo prisoner Khalid Qasim, still held without charge or trial, showing in "Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison," an exhibition at CUNY School of Law in New York.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work in 2020. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, February 21, 2020

For the men held in the U.S. government’s disgraceful prison at Guantánamo Bay, where men have now been held for up to 18 years, mostly without charge or trial, the U.S. authorities’ persistent efforts to dehumanize them — and to hide them from any kind of scrutiny that might challenge their captors’ assertions that they are "the worst of the worst" and should have no rights whatsoever as human beings — have involved persistent efforts to silence them, to prevent them from speaking about their treatment, and to prevent them from sharing with the world anything that might reveal them as human beings, with the ability to love, and the need to be loved, and with hopes and fears just like U.S. citizens.

Cutting through this fog of secrecy and censorship, "Guantánamo [Un]Censored: Art from Inside the Prison" is an exhibition of prisoners’ art that is currently showing in the Sorensen Center for International Peace and Justice at CUNY School of Law (City University of New York), based in Long Island City in Queens. The exhibition opened on February 19, and is running through to the middle of March. Entry is free, and anyone is welcome to attend.

As the organizers explain on the CUNY website, "The exhibit showcases artworks — the majority of which have never before been displayed — of eleven current and former Guantánamo prisoners, and includes a range of artistic styles and mediums. From acrylic landscapes on canvas to model ships made from scavenged materials such as plastic bottle caps and threads from prayer rugs, 'Guantánamo [Un]Censored' celebrates the creativity of the artists and their resilience."

The organizers also quote Moath al-Alwi, a Yemeni national and a client of CUNY Law School’s Immigrant and Non-Citizen Rights Clinic (INRC), who is one of the 40 men still held at Guantánamo, discussing what his artwork — the "model ships made from scavenged materials," mentioned above — means to him. As he says, "Despite being in prison, I try as much as I can to get my soul out of prison. I live a different life when I am making art."

The prisoners whose work is featured in the exhibition — represented by INRC, Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, Reprieve and the Center for Constitutional Rights — include six men still held — Khalid Qasim, Sabry Mohammed al-Qurashi, Towfiq al-Bihani, Ahmed Badr Rabbani and Assadulah Haroon Gul, as well as Moath al-Alwi — and five who have been released: Mohammed al-Ansi, Abdulmalik al-Rahabi, Ghaleb al-Bihani, Djamel Ameziane and Mansoor Adayfi.

As mentioned above, most of the artwork on display has not been seen before, but the works that have been seen were shown a little over two years ago at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, in a show, "Ode to the Sea: Art From Guantánamo Bay," that not only gave an insight into the prisoners’ humanity — and in some cases revealed genuine artistic talent — but also reflected well on the authorities at Guantánamo, who, after far too many years of preventing the prisoners from engaging in any kind of self-expression, had allowed men regarded as "well-behaved" to attend art classes.

All this good will, however, was shattered when the Pentagon, mistakenly inferring that current prisoners were seeking to sell their artwork, retaliated by threatening to destroy prisoners’ artwork, and to prevent them from making any more art in future. The Pentagon’s absurd overreaction was bad PR for them, making the show much more popular than it would have been, and attracting significant mainstream media coverage — and criticism of the Pentagon’s position. I wrote about it at the time, in a number of articles, including The Persistent Abuse of Guantánamo Prisoners: Pentagon Claims It Owns Their Art and May Destroy It, But U.S. Has Long Claimed It Even Owns Their Memories of Torture and The Guantánamo Art Scandal That Refuses to Go Away, and I reviewed the show, after I visited it in January 2018, here.

In the long run, however, the most lasting damage was at Guantánamo, where, although prisoners were allowed to resume making art, they were prevented from giving it to their lawyers, as gifts for them and for their families, a clampdown that has disillusioned and disincentivized many of the men, who were only interested in producing artwork if they were able to give it to those they were close to.

The CUNY show that has just opened is hugely important, as a renewed effort to show the prisoners as human beings, and also to highlight the unfairness of the Pentagon’s clampdown.

Although I missed the launch on February 19, I visited CUNY School of Law last month, when a version of the current exhibition was taking place, launched on January 11 (the 18th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo), which focused on the work on just one prisoner — Khalid Qasim (aka Khaled Qassim), whose case has long been of interest to me.

Of the 40 men still held, around half are regarded as "high-value detainees," and are held in a secretive facility known as Camp 7, while the rest of the men — the "lower-value detainees" — are held in the more public Camp 6, and while it would be a mistake even to accept that all the men identified as "high-value" are in fact of significance, the "lower-value detainees" very noticeably contain men who, by any objective analysis, don’t pose any kind of threat, having never been anything more than low-level foot soldiers in Afghanistan, recruited to take part in a long-running inter-Muslim civil war that, after 9/11, suddenly morphed into a war against the U.S.

Khalid Qasim is one of these men; only, it seems, regarded as a threat because, in his nearly 18 years at Guantánamo, brutalized in those early years, and never charged or tried for any kind of crime, he was a persistent hunger striker, and had what was perceived as a "bad attitude" to the circumstances of his imprisonment.

Guided by Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, who is co-counsel for Qasim and around ten other prisoners, I was able to appreciate his work far more than I would have, had I been left to my own devices. The photo at the top of this article, for example, is, quite literally, made of Guantánamo, consisting of gravel collected by Khalid from the prison’s recreation yard, mixed with broken-up MRE (Meals-Ready-to-Eat) boxes, and then glued in place. I found that very powerful conceptually, and was then quite moved when Shelby explained that the three red bars signify the three men who died on the night of June 9, 2006, in what the authorities called a suicide pact, but which numerous other people — including serving U.S. personnel at the base at the time — have suggested was a cover-up for the fact that they were killed.

Similarly, when it came to the image on the left, of a candle, I would not have realized that it, too, represented a prisoner who had died. Nine men have died in total at the prison since it opened in January 2002 — many under dubious circumstances, and all slandered in death by the authorities — and to commemorate them Khalid painted nine candles, each given to a member of his family. As Shelby explained, they were "taken off the base in groups of two and three," because Khalid "was afraid that paying respect to the deaths of his fellow prisoners would be silenced by the censors at Guantánamo."

Also on display were more classical paintings, heavily covered with primer so that they look like Renaissance paintings, showing symbolic or allegorical scenes relating to imprisonment, which, presumably, were taxing to the military’s art reviewers and censors, who were ridiculously paranoid that the men’s art might contain coded messages to Al-Qaeda. This was an absurd position when, more logically, what they were far more likely to contain — if they strayed off the innocuous picture postcard scenes chosen as subjects by many of the prisoners — would be oblique commentaries about the dreadful circumstances of their confinement, rather than any terrorist connection that never existed in the first place.

The painting shown here was, as Shelby explained, made "as a metaphor for the life [Khalid] is missing while imprisoned in Guantánamo: the kettle pouring coffee is meant to represent his home in Aden, Yemen; the stream of coffee missing the cup represents the culture he is missing, leaving him empty."

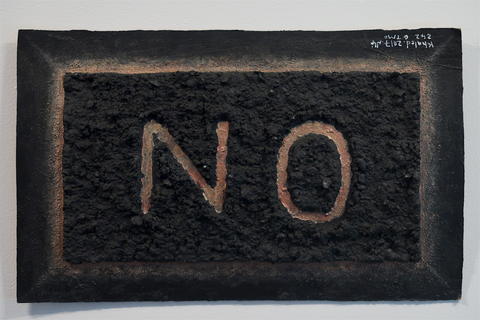

The last of Khalid’s artworks I’m posting is his bold statement of a single word — "No" — which he explained in an unclassified note to Shelby in May 2017. As he put it, "I refuse oppression of any kind from anyone even if it is from those closest to me. I strongly expressed my objection when I was forcefully taken out of my cell for feeding. Before the F.C.E. [forced cell extraction] camera (and in the presence of guards, medical staff, high ranking officials and my fellow detainees), I said NO to unjust rules, NO to giving in and NO to giving up."

If you’re in the New York area, I hope you can make it to the show, which I hope will continue to run in various permutations on an ongoing basis. I intend to post more pictures and stories, and I hope that, if you find the work — and what it says about the men creating it, and the circumstances in which they find themselves — to be of interest, then you will share it as widely as possible.

This work remains as powerful as it was when some if it was shown at John Jay College over two years ago, and the more it is in the public eye, the more the authorities will struggle to maintain their illusion that the prisoners at Guantánamo are some kind of super-human terrorists, "the worst of the worst," and not human beings, who love, and feel loss and pain, just like us, and who, in many cases, did nothing to harm the U.S., and yet have been deprived of their liberty for up to 18 years in a horrible experimental facility where the normal rules of imprisonment don’t apply.