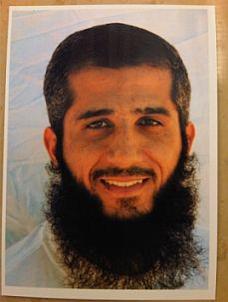

Guantánamo Review Boards Clear Kuwaiti Prisoner Fawzi Al-Odah for Release, But Defend Ongoing Imprisonment of Fayiz Al-Kandari

Fawzi al-Odah, in a photo included in the classified military files from Guantánamo released by Wikileaks in 2011.

By Andy Worthington, July 30, 2014

On July 14, the board members of the Periodic Review Boards at Guantánamo -- consisting of representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff -- approved the release of Fawzi al-Odah, one of the last two Kuwaiti prisoners in Guantánamo, but recommended that the other Kuwaiti, Fayiz al-Kandari, should continue to be held.

This is good news for Fawzi al-Odah, but the decision about Fayiz al-Kandari casts a dark cloud over the whole process. I have been covering the stories of both men for many years, and it remains as clear to me now as it always has been that neither man poses a threat to the US. Here at "Close Guantánamo," we profiled both men back in February 2012, shortly after Tom Wilner and I, the co-founders of the "Close Guantánamo" campaign, had been in Kuwait trying to secure their release (see here, here and here).

The Periodic Review Boards were established last year, to review the cases of 46 Guantánamo prisoners specifically detained on the basis that they are allegedly too dangerous to release, even though insufficient evidence exists to put them on trial.

The decisions about the supposed danger posed by the men -- despite the lack of evidence against them -- were taken by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama appointed to review the prisoners' cases shortly after he took office in 2009, and when he implemented the task force's recommendations in March 2011, in an executive order authorizing the specific imprisonment without charge or trial of these 46 men, he promised that there would be periodic reviews of their cases to establish whether or not they continued to be regarded as a threat.

This is the process that only belatedly began last November, after 25 other prisoners were added to the list of those eligible for PRBs. These 25 had initially been recommended for prosecution by the task force, but had been withdrawn from consideration for trials when two appeals court rulings, in October 2012 and January 2013, dealt a major blow to the credibility of the military commissions -- the trial system chosen for the Guantánamo prisoners under President Bush, and continued under President Obama -- by overturning two of the only convictions secured in the commissions' lamentable post-9/11 history.

Since the Periodic Review Boards began, nine prisoners have had their cases reviewed. Decisions have not yet been taken in the cases of two of these men -- Muhammad al-Shumrani and Muhammad al-Zahrani -- but of the seven others, four, including Fawzi al-Odah, have now been recommended for release (see here and here and here), while three others, including Fayiz al-Kandari, have been recommended for ongoing imprisonment on the basis that "continued law of war detention … remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States" (see here and here).

Prior to the decision in al-Odah's case, all of the men recommended for release were Yemenis, who have not been released because the entire U.S. establishment is fearful about the security situation in Yemen. This is completely unacceptable, as it is more damaging to America's reputation for justice to continue holding men cleared for release than to free them, but in al-Odah's case the restrictions do not apply, and it is likely, therefore, that he will be freed soon.

In al-Odah's case, the board concluded that "continued law of war detention … does not remain necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States," and added that, in making its determination, the board noted his "low level of training and lack of a leadership position in al-Qaeda or the Taliban" and his "personal commitment to participate fully in the Government of Kuwait's rehabilitation program and comply with any security measures, as well as [his] extensive family support."

The Board also found al-Odah's "statements to be credible regarding his commitment not to support extremist groups or other groups that promote violence, and noted the positive changes in [his] behavior while in detention." The board also "considered information provided by the Government of Kuwait that indicated its confidence in its legal authority to require and maintain [his] participation in a rehabilitation program and commitment to implement robust security measures." This, the board noted, includes al-Odah's "participation in a full rehabilitation program for at least one year of in-patient rehabilitation."

Fayiz al-Kandari, in a photo taken at Guantánamo in 2009 by representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

In al-Kandari's case, unfortunately, although the board found him "credible with respect to his desire to return to his family, which appears willing to help with his reintegration," the board members also decided that he "almost certainly retains an extremist mindset and had close ties with high-level al-Qaeda leaders in the past," even though there is no evidence for either claim. As I explained back in 2009 in a major profile of al-Kandari, his history is one of caring for others and engaging in charitable activities, and the allegations of his involvement with al-Qaeda simply do not stand up under scrutiny, as he arrived in Afghanistan in August 2001, and had no time to do any of the things of which he has been accused -- which, absurdly, include a claim that, in a ridiculously short amount of time, he became a spiritual adviser to Osama bin Laden.

In attempting to justify their decision, the board considered that al-Kandari had a "susceptibility for recruitment" to terrorism "due to his connections to extremists and his residual anger at the US," and also "noted a lack of history regarding the efficacy of the rehabilitation program Kuwait will implement for a detainee with his particular mindset." What I find alarming about this conclusion is the suggestion that al-Kandari's resentment at losing 12 years of his life in Guantánamo is somehow unacceptable, when it is surely understandable to be angry, and this, in itself, is a not the same thing as being so angry that you engage in terrorism when released -- something that, I can confidently say, having heard so much about him and having met his large extended family, would never happen in his case.

The board added that it "appreciates the efforts of the Kuwaiti government and encourages the officials at the AI Salam Rehabilitation Center" in Kuwait, a facility funded by the Kuwaiti government solely for al-Odah and al-Kandari, to "continue to work with" al-Kandari, presumably through correspondence.

His case will be reviewed in six months, and the board members expressed their hope that he would remain involved in the process.

Here at "Close Guantánamo," we hope so too, but we also understand why Fayiz al-Kandari might be reflecting that there is no justice at Guantánamo. As his military defense lawyer Barry Wingard wrote back in In July 2009, in an op-ed for the Washington Post:

Each time I travel to Guantánamo Bay to visit Fayiz, his first question is, "Have you found justice for me today?" This leads to an awkward hesitation. "Unfortunately, Fayiz," I tell him, "I have no justice today."