The U.S.’s Ongoing “Forever Prisoner” Problem at Guantánamo

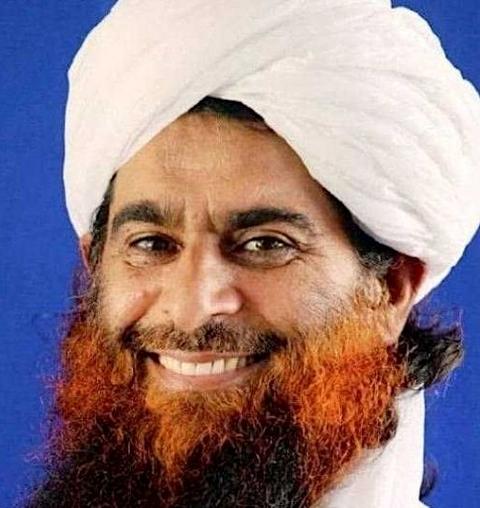

A recent photo of Afghan prisoner Muhammad Rahim at Guantánamo, taken by representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, and made available by his family.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work in 2022. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, May 17, 2022

It’s now over 20 years since, in response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the Bush administration declared that it had the right to hold indefinitely, and without charge or trial, those seized in the "war on terror" that was launched after the attacks.

As a result of the U.S. turning its back on laws and treaties designed to ensure that people can only be imprisoned if they are charged and put on trial, or held until the end of hostilities as prisoners of war, the men held in the prison at Guantánamo Bay have struggled to challenge the basis of their imprisonment.

For a brief period, from 2008 to 2010, the law actually counted at Guantánamo, after the Supreme Court ruled that the prisoners had constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights, and 32 men were freed because judges ruled that the government had failed to establish — even with an extremely low evidentiary bar — that they had any meaningful connection to either Al-Qaeda or the Taliban. However, this brief triumph for the law came to an end when politically motivated appeals court judges passed a number of rulings that made successful habeas petitions unattainable.

Ironically, the only other prisoners freed because the law applied to them were a handful of men charged in the military commissions, the trial system that was unwisely dragged out of the history books by the Bush administration. Between 2007 and 2014, eight men were convicted, mostly through plea deals, with all but two subsequently released, leading to a situation whereby it was easier to get released from Guantánamo through being regarded as "significant" than by being a "low-level" prisoner.

For the majority of the 732 men who have been freed from Guantánamo since the prison opened in January 2002, the law has had no influence on their release. After he chaotically established Guantánamo in the first place, George W. Bush freed 532 men before he left office, many as a result of political pressure from their home countries, while others were freed as a result of administrative review processes introduced in 2004.

Under Obama, this trend towards administrative reviews continued. Having inherited 240 prisoners from Bush, Obama set up a high-level government review process, the Guantánamo Review Task Force, whose members met once a week throughout 2009 to decide whether to recommend the men still held for release, for trials, or, in some cases. for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial, on the basis that the men in question were "too dangerous to release," but insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial. 156 men were recommended for release, and all but three of them were eventually freed.

The rest, however, were either consigned to the military commissions, which became an increasingly broken imitation of a functioning judicial system, or were reassigned to another review process, the Periodic Review Boards. This was a parole-type system, in which, if the men in question were able to demonstrate contrition, and coherent plans for a peaceful life after Guantánamo, they were approved for release.

64 men had their cases reviewed by PRBs under Obama, and 38 men were approved for release. All but two of these men were transferred out of the prison before Obama left office, and the other two have finally been freed by President Biden, who, after four years of shameful inertia under Donald Trump, inherited 40 prisoners when he took office in January 2021 — 12 charged or convicted in the military commissions, three approved for release by the Guantánamo Review Task Force, three approved for release by the PRBs, and 22 others — accurately described as "forever prisoners" in the mainstream media — whose ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial had been recommended by the PRBs.

To his credit, President Biden has recognized — helped by international criticism of Guantánamo, and criticism by 99 of his own Senators and Representatives — that holding men indefinitely without charge or trial is fundamentally unacceptable, and as a result, the revived PRB process has approved 17 men for release since he took office — although only one of them has, to date, been freed.

This leaves just five "forever prisoners" at Guantánamo, but that is five too many, if Biden is serious about bringing to an end the unforgivably long flight from the law that began when Guantánamo opened, indefinitely holding men without charge or trial, just as a dictatorship would.

The five "forever prisoners" are: Khaled Qassim (aka Khalid Qasim), a Yemeni; Abu Zubaydah, for whom the CIA’s disgraceful post-9/11 torture program was first introduced; Ismael Ali Faraj Ali Bakush, a Libyan; Mustafa Faraj al-Usaybi (aka Abu Faraj al-Libi), another Libyan, who was also held and tortured in CIA "black sites"; and Muhammad Rahim, an Afghan, who was the last prisoner to arrive at Guantánamo, in March 2008, after also being held in "black sites." Of the five, Zubaydah, al-Usaybi and Rahim are all "high-value detainees," held separately from the general prison population, to which Qassim and Bakush belong.

The problem for Biden is what to do with these men if PRBs keep refusing to recommend their release, as has happened with two of them over the last five months. At the end of December, a PRB approved the ongoing imprisonment of Khaled Qassim, who was never anything more than a low-level fighter with the Taliban, because he wasn’t regarded as compliant enough, and on April 19 Muhammad Rahim also had his ongoing imprisonment upheld.

The case of Muhammad Rahim

The board "considered that [Rahim] was a trusted member of Al Qaeda who worked directly for senior members of Al Qaeda, including Usama bin Ladin [sic], serving as a translator, courier, facilitator, and operative." They also claimed that he "had advanced knowledge of many Al Qaeda attacks, to include 9/11, and progressed to financing, planning, and participation in attacks in Afghanistan against U.S. and Coalition targets."

Moving on to his perceived mindset, the board "considered [his] extensive extremist connections and consistent and long-standing expressions of support for extremism that provide a path to re-engagement, and [his] continued non-compliant behavior and anti-American expressions in detention." They also stated that his "unwillingness to discuss pre-detention activities and beliefs prevented the Board from assessing whether he has had any change in mindset or level of threat."

In contrast to the above, those representing Rahim paint a very different picture. Although his attorney’s submission to his most recent PRB was not made public, his personal representative (a military official assigned to represent him) noted that he "has been consistent in attending meetings," and that he has family members who "are waiting to provide support for [him] and assist him in returning to a peaceful life with his family," as well as having "the support of leaders and elders" in his home province.

The personal representative also hinted that Rahim may have had reasons for his unwillingness to discuss his past, stating that Rahim and his attorney were "in agreement that he [would] answer only questions looking forward and [would] politely refuse to answer questions of his past activities prior to his capture," and it’s possible, therefore, that Rahim’s reticence relates perhaps to considerations regarding his safety rather than anything more malign.

Moreover, previously reported aspects of Rahim’s story suggest a very different person to the hardcore jihadist portrayed by the PRB. In 2017, Major James Valentine, a military defense attorney assigned to him in case he was ever to be charged in the military commissions, submitted a petition on his behalf to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, in which he stated, "The United States has never released credible evidence that Mohammad Rahim was a combatant, a terrorist or an important member of Al-Qaeda or the Taliban. By all accounts, he was merely a local Afghan whose ancestral village was located near the mountainous areas in Nangarhar province where Al-Qaeda was operating before December 2001. The worst allegation against Mohammad Rahim is that he served as a Pashto translator, 'facilitator,' and guide to the Arabs who belonged to Al-Qaeda. All of the evidence against him is highly secretive, contradictory, lacking in credibility and inherently unreliable as it was coerced during detainee interrogations. It is unknown how much of it was derived from torture."

Maj. Valentine added that Rahim "never belonged to either Al-Qaeda or the Taliban," and was, instead, "politically loyal to Hezb-I-Islami," whose leader, Gulbuddin Hekmaytar, had "recently signed peace agreements with the government of Afghanistan" and had "agreed to share in the peaceful governance of the nation." This was all true, and, in fact, before the Taliban resumed power in Afghanistan, following the U.S. withdrawal in 2021, former Guantánamo prisoners connected to Hekmatyar’s organization had been repatriated from the UAE, where they had been sent when they had been released from Guantánamo following their own PRBs.

While membership of Hekmatyar’s organization ought not to be a reason for continued imprisonment at Guantánamo, Rahim has also demonstrated a distinctly un-jihadist interest in popular culture while at Guantánamo.

As I explained when his PRB endorsed his ongoing imprisonment in 2016, in 2012, his attorney at the time, Carlos Warner, a federal public defender for the Northern District of Ohio, released letters that showed a different side to his client than the associate of bin Laden described by the U.S. authorities. In one letter, Rahim wrote, "I like this new song Gangnam Style. I want to do the dance for you but cannot because of my shackles."

Warner described Rahim’s comment and others as showing that "he's different and he's intelligent," and that he "has an incredibly good sense of humor," and, at the time of his 2016 PRB, explained to the Miami Herald that the board "didn’t get the full picture" because he — Warner — "wasn’t allowed to participate in his client’s hearing," for reasons that were not explained.

As Warner also explained, however, Rahim "had no knowledge about 9/11 in advance," and is, instead, "being held because he was in a black site, not because of what he did. if he did those things, why didn’t they charge him?" As I stated at the time, these are "all valid comments and questions, with which I concur." If the U.S. government’s roll call of allegations is remotely verifiable, surely Rahim should have been put forward for a military commission trial, and the fact that he hasn’t indicates that, as is so often the case with Guantánamo, rumors and innuendo are apparently regarded as an adequate substitute for anything resembling facts.

The remaining "forever prisoners"

While Khaled Qassim has another opportunity to impress a PRB today (May 17), Muhammad Rahim will have to wait a few years before he has another opportunity to seek his release, a situation that is not only unacceptable in terms of its legitimacy, but that also ignores fears about his health, with Al-Jazeera reporting in December 2020 that medical examinations had "uncovered several 'nodules' in his lung, liver, kidney and rib, raising fears of cancer," and that, although the authorities had agreed to let him have an MRI scan, that offer was later withdrawn.

As for the remaining "forever prisoners," Ismael Bakush is awaiting a decision following a review on March 22, while Mustafa al-Usaybi has a review scheduled for June 23. Abu Zubaydah, meanwhile, had his most recent review on July 15 last year, but no decision has yet been taken.

Bakush is accused of being a member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, opposed to Colonel Gaddafi, and of being an "explosives expert who trained al-Qa’ida members and probably provided support to key al-Qa’ida figures," although the unidentified sources responsible for these claims have also noted that he "has consistently denied his close association with al-Qa’ida and expertise with explosives." The board, however, has assessed that he "played a greater role in al-Qa’ida operations than he admits."

Back in 2016, when a PRB upheld his ongoing imprisonment, the board noted his "lack of candor and evasive, implausible, and frequently absurd responses to questions regarding his past, activities, and beliefs," which does not augur well for his recent hearing, and his situation also appears to be complicated by the fact that he has been so disillusioned with the situation at Guantánamo for so many years that he has not seen his attorney since 2013.

Al-Usaybi, meanwhile, who, for his last review in 2019, was described as someone who had "traveled to Afghanistan to fight at a young age, joined al-Qa'ida, and rose through al-Qa'ida's hierarchy to become the group's general manager and a trusted adviser for and communications conduit to Usama Bin Ladin and deputy amir Ayman al-Zawahiri," has persistently refused to engage with the PRB process, not only boycotting it during the Trump years (when most prisoners boycotted the hearings, having correctly concluded that, under Trump, the PRBs had become a sham), but also boycotting it in 2016. As a result, very little is known about him, but if there is a case against him then the authorities should charge him in the military commissions.

And finally, of course, there is Abu Zubaydah, whose case is, perhaps, the most shockingly brutal and counter-productive in the whole of the "war on terror." Seized in a house raid in Pakistan in March 2002, Zubaydah, whose real name is Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn, was subjected to shocking torture in CIA "black sites," as described in unprecedented detail in "The Forever Prisoner," the recently published book by Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy.

Abu Zubaydah was mistakenly thought of as the number three in Al-Qaeda, when he was actually a facilitator for a training camp that was specifically not aligned with Al-Qaeda, but his torture was so extreme that the CIA sought reassurances that, if he didn’t die as a result of the torture to which he was subjected, he would "remain in isolation and incommunicado for the remainder of his life."

That has not quite come to pass, as Abu Zubaydah is represented by a number of attorneys who have been allowed to visit him over the years, but none of them can discuss his case freely, and Zubaydah himself remains isolated, as the CIA intended, and largely without a voice. Noticeably, however, the case against him has steadily collapsed over the years, as the U.S. authorities have conceded that he wasn’t a member of Al-Qaeda, and that he had no knowledge of the 9/11 attacks.

For his review last summer, the authorities focused instead on his role as a facilitator for the Khaldan camp, which was independent of Al-Qaeda, making reference to the latter only through a claim that he "probably had served as one of Usama bin Ladin’s most trusted facilitators as early as the mid-1990s, although he said that he never swore bay’ah [a pledge of allegiance] to him because of his primary focus on attacking the U.S., and Zubaydah wanted to attack Israel for its treatment of Palestinians."

For his review, Mark Denbeaux, one of his attorneys, submitted a statement in which he concluded, accurately, that the "[t]ruth requires that Abu Zubaydah be set free," but it remains to be seen, of course, if the U.S. authorities can admit the extent of their mistaken depravity in his case, and can restore some semblance of his life to him — although if they do, they will need to do so with resolute frankness, because, for Abu Zubaydah to leave Guantánamo, a third country must be found that will be prepared to take him in. Although born and raised in Saudi Arabia, Abu Zubaydah’s parents were Palestinian, and were therefore not granted Saudi citizenship, and, as anyone who has studied Guantánamo’s history will know, no Palestinian held at Guantánamo has ever been repatriated, because the Israeli government is the gatekeeper, and has never even contemplated accepting the return of a single Palestinian from Guantánamo.

I don’t know where Abu Zubaydah will end up, but I do know that it is intolerable that he — and the other "forever prisoners" still held at Guantánamo — continue to be held indefinitely without charge or trial. All of them must eventually be released, unless, as has always been an option, the U.S. authorities conclude that, despite years of failing to do so, they can put together a credible case against them, and put them on trial.