97-Pound Yemeni Hunger Striker Appears Before Periodic Review Board As Saudi is Approved for Release from Guantánamo

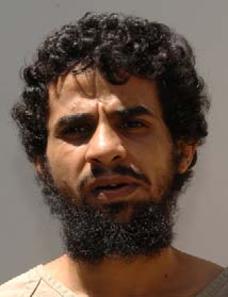

Muhammad al-Shumrani, a Saudi approved for release from Guantánamo by a Periodic Review Board in September 2015, in a photo taken at Guantánamo and included in the classified military files released by WikiLeaks in 2011.

By Andy Worthington, September 29, 2015

After months of inaction on Guantánamo, there has, in recent weeks, been a flurry of activity, with two prisoners released (one to Morocco and one to Saudi Arabia), and with the approval of two prisoners for release by Periodic Review Boards (Omar Mohammed Khalifh, a Libyan, and Fayiz al-Kandari, the last Kuwaiti in the prison, who was recommended for ongoing imprisonment by a PRB last year, but was given a second opportunity in July to persuade the board that he is no threat to the United States, which was successful).

On Friday, it was also revealed that Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in Guantánamo, who we have written about extensively here, will be freed within the next month, and it is expected that a Mauritanian, Ahmed Ould Abdel Aziz, long approved for release like Shaker, will also be freed soon, along with two the prisoners whose cases are with defense secretary Ashton Carter, but who have not been publicly identified.

Adding to all this news, last week -- largely unnoticed in the media -- another prisoner was approved for release by a Periodic Review Board, the review process established two years ago to review the cases of all the men who were not previously approved for release by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office, and who are not facing trials.

Most were regarded as "too dangerous to release" by the task force, which also acknowledged, however, that there was insufficient evidence to put them on trial -- meaning, of course, that it was not evidence at all, but a collection of dubious tainted evidence from the widespread torture and abuse of the "war on terror." Others were initially recommended for trials, until the military commissions began to seriously unravel.

Muhammad Al-Shumrani, a Saudi, is approved for release

19 prisoners have so far had their cases reviewed. Four cases have not been decided yet, but of the 15 others all but two have ended up with the review boards recommending their release. Two of those decisions took place on the second review -- in the case of Fayiz al-Kandari, who was recommended for release on September 8, and, as revealed last week, in the case of Muhammad Abd al-Rahman al-Shumrani, a Saudi, whose case was first reviewed last May.

In al-Shumrani's case, he had refused to attend his PRB, which involves representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, communicating by video-link with Guantánamo, because of the humiliating and intrusive body searches that take place when prisoners are moved from one part of the prison to another.

That unwillingness to take part had clearly not impressed the board, but after his second PRB, in August, the board members concluded, in a decision delivered on September 11, that "continued law of war detention … does not remain necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States."

The board added that they "acknowledged the detainee's past terrorist-related activites and connections but determined [his] threat can be adequately mitigated by Saudi Arabia." Specifically, the board noted, they had "confidence in the efficacy of the Saudi rehabilitation program and Saudi Arabia's ability to monitor the detainee after completion of the program," and they also "found the detainee credible on his desire to participate in the program.'"

They also noted his "strong desire to engage in scholarly religious discussion and receive guidance from clerics at the rehabilitation centre about Islam and his willingness to submit to the authority of the Saudi government." The board also noted that al-Shumrani had been "candid with the board, including regarding his presence on the battlefield and world view, and articulated a commitment to fulfilling his role within his family over taking up arms or continuing to engage in jihad."

The Miami Herald noted that al-Shumrani’s attorney, Martha Rayner, said in an email that he "looks forward to participating in the Saudi rehabilitation program and reuniting with his family." The newspaper also picked out a comment made in August by his personal representatives (military personnel appointed to represent him), who noted that he had "slipped quietly into middle age" during his 13 years at Guantánamo.

If the cases of Muhammad al-Zahrani and Abdul Rahman Shalabi, the other two Saudis approved for release by a PRB, are anything to go by, al-Shumrani will be repatriated sometime in the next few months, making him one of the more fortunate prisoners at Guantánamo. Just three of the 13 men so far approved for release by PRBs have been freed -- a Kuwaiti and the two Saudis mentioned above. The others awaiting release include six Yemenis, to add to the 37 other Yemenis approved for release by the task force, back in 2009, but still held. A refusal to repatriate Yemenis, shared across the entire U.S. establishment, means that these men cannot be freed until third countries are found for them, and this is a slow process.

The case of Moath Al-Alwi, a Yemeni hunger striker weighing just 97 pounds

On September 22, another Yemeni, Moath al-Alwi (aka Muaz al-Alawi) became the 18th prisoner to appear before a Periodic Review Board. I have written about his case extensively over the years. In 2009, his habeas corpus petition was turned down, because, as I explained when his appeal was also turned down later that year:

Although al-Alawi was in Afghanistan before the 9/11 attacks, and was fighting with the Taliban against the Northern Alliance, Judge Leon ruled that he was an “enemy combatant” because he endorsed the government’s claim that, “rather than leave his Taliban unit in the aftermath of September 11, 2001,” al-Alawi “stayed with it until after the United States initiated Operation Enduring Freedom on October 7, 2001; fleeing to Khowst and then to Pakistan only after his unit was subjected to two-to-three US bombing runs.”

In other words, as I described it when al-Alwi's habeas petition was turned down:

Judge Leon ruled that Muaz al-Alawi can be held indefinitely without charge or trial because, despite traveling to Afghanistan to fight other Muslims before September 11, 2001, “contend[ing] that he had no association with al-Qaeda,” and stating that “his support for and association with the Taliban was minimal and not directed at US or coalition forces,” he was still in Afghanistan when that conflict morphed into a different war following the US-led invasion in October 2001. As Leon admitted in his ruling, “Although there is no evidence of petitioner actually using arms against US or coalition forces, the Government does not need to prove such facts in order for petitioner to be classified as an enemy combatant under the definition adopted by the Court.”

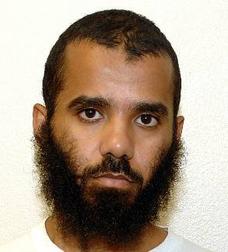

Moath al-Alwei (aka Muaz al-Alawi), in a photo taken at Guantánamo and included in the classified military files released by WikiLeaks in 2011.

Al-Alwi's case was later turned down by the Supreme Court (in 2012), and the following year he was part of the prison-wide hunger strike that drew international criticism for President Obama's loss of interest in Guantánamo in the face of Congressional opposition. He continued his hunger strike after most of his fellow prisoners had given up, and, last year, complained to his lawyer, Ramzi Kassem of the City University of New York: "It is all political. It is all theater, it is all a game." Earlier this year, his lawyers sought a new avenue to his release, submitting his case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and in June he wrote an op-ed for Al-Jazeera asking why he was still held, after President Obama had declared that the war in Afghanistan was over.

Writing about al-Alwi's case, Human Rights First noted that he "was captured in 2001 by Pakistani authorities alongside a group identified as the 'Dirty 30' – a name given to them because of allegations that they had served as bodyguards for Osama bin Laden. However, these allegations were primarily based on statements by Mohammed al-Qahtani -- a detainee who had been tortured at Guantánamo and who later withdrew his false allegations -- and confessions by two other detainees that a US court recently proved false. In fact, only three of the 'Dirty 30' have any substantiated allegations relating to al Qaeda involvement."

In fact, the government has clearly walked back from much of its former hyperbole about the "Dirty 30." In the profile of al-Alwi for his PRB, he was described as "an al-Qa'ida-affiliated fighter who spent time with Usama Bin Ladin's security detail but probably was not one of Bin Ladin's bodyguards." It was also claimed that he "probably trained with al-Qa' ida, and possibly helped manage an al-Qa' ida guesthouse" (italics added to emphasize the vagueness of the claims) and also allegedly "developed relationships with many prominent extremists in Afghanistan and spent time with al-Qa'ida and Taliban fighters on the frontlines, although we do not know whether he engaged directly in combat." It was also noted that he "has caused a great deal of trouble for the staff" at Guantánamo, and has frequently expressed anti-American sentiments, although whether that proves anything is open to question. 23 years old at the time of his capture, he is now 36 years old, and has lost a third of his life in brutal and lawless conditions that would make many people angry.

The PRBs, however, demand compliance as a key to release -- or, at least, being recommended for release, and it must be reassuring, therefore, that his lawyer was able to tell the board that his client’s current disciplinary status is "compliant," even though he is still on a hunger strike. As Human Rights First described it, he "had communicated to his personal representatives that he was willing to try and transition back to a normal diet of solid food," but when "a PRB member asked why this transition had not occurred," his lawyer explained that his client lacked the necessary medical support.

Below I'm posting the opening statements of al-Alwi's personal representatives, and of his lawyer, Ramzi Kassem, which, I believe, explain his desire to rebuild his life, and also indicate a possible route out of Guantánamo should the board members agree -- the fact, as Ramzi Kassem explains, that although he is a Yemeni citizen, he was born and raised in Saudi Arabia, where almost the whole of his family still lives, and he could, therefore, be easily sent back there.

The most shocking information, however, to my mind, is the fact that he weighs just 97 pounds -- and if a photo of him at this weight were to be released to the general public, there would, I am sure, be an outcry, and a demand for his immediate release and the closure of Guantánamo.

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 22 Sep 2015

Moath Hamza Ahmed Al-Alwi ISN 28

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Ladies and gentlemen of the Board, good morning. We are the Personal Representatives for Moath al-Alwi, ISN 028. In our submission, we have provided you with information that demonstrates Mr. al-Alwi does not pose a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States. His family is ready to provide support after his transfer, and most importantly, he is willing to attend a rehabilitation program and live his life in peace.

As Moath's Personal Representatives, we've met with him face to face on more than a dozen occasions over the course of several months. Throughout our interactions, we have found him to be polite, sincere and pleasant. He has proven that he has a well-developed set of ethics and a sharp sense of right and wrong. Moath has been on hunger strike over the majority of the past several years. This has affected his health to the point where he can no longer eat a normal diet without adverse reactions. During our first meeting we asked him to attempt a transition back to a normal diet of solid food to improve his case for transfer and for his own well-being. Moath did not immediately agree to do this. However, he later sent us a message stating he would try if his representatives thought it was good for him.

Moath's Personal Counsel, Ramzi Kassem, has met with and had regular contact with Moath's family members, most notably his father and eldest brother. Moath's brother has living space and a job waiting for him when he is transferred from Guantánamo. Additionally, his sister has a business of her own and has saved money to assist with Moath's transfer, education and training. She has also agreed to assist Moath by providing start-up funds for a business when the time arises.

Personally, Moath would like to live near his family again and, eventually, start a family of his own. More than that, however, he wants to attend a rehabilitation and training center, where he will have the opportunity to continue his education. His ultimate goal is to pursue a college degree in engineering. Moath understands he needs skills if he's to succeed with a career, a family, and a normal life. With limited resources available at Guantánamo, he's taught himself to make cardboard furniture, how to paint, and among his favorites, how to garden. He becomes excited when discussing the possibility of learning to be a construction engineer, landscape architect or artist.

Moath is frustrated by his nearly 14 years of detainment without trial, as any reasonable human would be. However, he believes this is a function of politics, world unrest, and his citizenship. He does not believe that Guantánamo is representative of the American people or the American way of life. Notably, Moath remarked to us that he would eagerly agree to a transfer to the United States, should that ever become a possibility. He stated that living in the United States would open opportunities for education and employment that were never available to him before in his life.

Moath has demonstrated that he is open minded and willing to change when he sees hope of a better future. He is 36 years old and wishes to begin to live his life again as soon as possible. The effects of his hunger striking over the years have damaged his health to a great extent. He wishes to put this all behind him and build a normal, healthy life outside Guantánamo. Accordingly, we do not believe that Moath is a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.

Statement by Prof. Ramzi Kassem, Private Counsel for Moath al-Alwi (ISN 028)

Periodic Review Board Hearing Scheduled September 22, 2015

Esteemed Periodic Review Board Members,

I serve as pro bono counsel to Moath al-Alwi (ISN 028) before the Periodic Review Board as well as in U.S. federal court. I have represented Mr. al-Alwi since 2009. I write to provide additional information to inform your decision as to whether Mr. al-Alwi "constitutes a significant threat to the security of the United States."

From the outset, it is worth emphasizing that although he has been in U.S. custody at Guantánamo Bay since 2002, there is no evidence or accusation that Mr. al-Alwi ever fought against the United States or any other party. Moreover, he has not been charged nor found guilty of any crime.

A Yemeni citizen born and raised in Saudi Arabia, Mr. al-Alwi traveled to Afghanistan in early 2001 to teach the Quran and live in a society that appeared from afar to honor Islamic ideals. He was 24 when he fled the conflict there, was seized by the authorities in Pakistan and likely sold into American captivity for a bounty.

At a 2008 hearing, having given Mr. al-Alwi only three weeks to review a lengthy dossier compiled by the U.S. government over seven years, a federal judge ruled his detention justified. A court of appeals found that the judge's "haste" was hard to understand," but upheld the decision. The U.S. Supreme Court then declined to receive Mr. al-Alwi's final appeal. Mr. al-Alwi has recently filed a second habeas corpus petition in U.S. federal court which is now pending.

Even if one were to credit unverified U.S. intelligence reports that form part of the unclassified and public record in his federal habeas corpus case, Mr. al-Alwi allegedly obtained less than one full day's training at a training camp near Kabul, Afghanistan. He was never hostile to the United States and bears no ill will towards it today.

While at Guantánamo, Mr. al-Alwi has gone on hunger strike on more than one occasion, which has caused his health to deteriorate rapidly. He absolutely does not wish to kill himself, as his religion prohibits suicide. But despite the terrible toll it has taken on his health, Mr. al-Alwi chooses not to eat as a form of peaceful, non-violent protest against his continuing imprisonment at Guantánamo and against some of the conditions of his confinement.

These include humiliating groin searches, especially when prisoners are taken for phone calls with their lawyers or families; withheld medical treatment; confiscated legal papers and Qurans: solitary confinement: and other forms of unduly harsh treatment.

In response to Mr. al-Alwi's hunger strike, the prison administration at Guantánamo has chosen to force-feed him daily in a restraint chair.

It is important to highlight that hunger striking is one of a few forms of control that Mr. al-Alwi and other prisoners retain over their lives. Moreover, like sit-ins, hunger striking is a form of peaceful and civil disobedience, not a crime under domestic or international law. It is Mr. al-Alwi's way of demanding the attention of the U.S. government holding him captive, of the American people to whom it is beholden, and of concerned citizens the world over.

Mr. al-Alwi knows that governments do not always act in accordance with the values and views of their people. His hunger strike rests on the belief that the American people, if they knew, would not condone his continued imprisonment or the conditions of his confinement.

Mr. al-Alwi fully recognizes that people outside of prison might find his hunger strike difficult to comprehend. His own family certainly does. His mother tells me that she spends much of her rare phone calls with him pleading that he stop his hunger strike. But Mr. al-Alwi sees it as the only way he has left to cry out for life, freedom and dignity.

Today, Mr. al-Alwi's disciplinary status at Guantánamo is "compliant." He is not on punishment status and he presents voluntarily for tube-feeding and to be weighed (he currently weighs approximately 97 pounds).

My present understanding is that Mr. al-Alwi intends to finally end his hunger strike if he is approved for release by the Periodic Review Board. This would also doubtless please his mother. Understandably, he is concerned about readjusting to a normal diet here at Guantánamo and hopes that he would receive the necessary medical and dietary support to make that transition safely and smoothly.

If released from Guantánamo, Mr. al-Alwi intends to learn a professional skill or develop one of the skills he acquired in prison in order to rebuild his life. At Guantánamo, Mr. al-Alwi excelled in the art classes that were offered. He learned to use cardboard to fashion shelves, drawers, small tables. and other furniture, to rave reviews from fellow prisoners and the guard force alike.

Mr. al-Alwi also taught himself how to make sweets and other treats, which he offers to fellow prisoners and guards. He has prepared kunafah, an Arab dessert, and has even developed his own version of Snickers bars. Many guards cannot believe that he is able to make these treats on the cellblock using only the limited ingredients at hand.

Another prisoner who used to be a professional cook even assured Mr. al-Alwi that, with his skills. he could open a business. Recently I learned that one of Mr. al-Alwi's sisters had asked him for one of his recipes during a phone call and that he had refused jokingly telling her that he couldn't just give up his "trade secrets."

Mr. al-Alwi loves the art lessons and the computer lessons he has been able to take at Guantánamo. Unfortunately, however, he has found the English lessons less useful as they are often taught by interpreters who are not themselves fully bilingual or trained to teach English as a second language. Also, his disciplinary status sometimes prevented him from enrolling in classes.

Of course, once a free man, Mr. al-Alwi also wishes to marry and start a family.

His most immediate wish, however, is to regain his freedom, be it in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, where he was born and raised and where his family still resides or in any third country that the U.S. government deems suitable.

Should Saudi Arabia accept Mr. al-Alwi he would gladly partake in its Interior Ministry's well-established Counseling & Rehabilitation Program with the full support and cooperation of his family.

Indeed Mr. al-Alwi's entire family has resided legally in Saudi Arabia for decades. He only has a few relatives remaining in Yemen and among them he only knows his elderly maternal aunt.

In Saudi Arabia, Mr. al-Alwi has two brothers and three sisters, all in Jeddah. One of his brothers is a small scale merchant. He is married with three sons. His other brother is still a student. Their father is a car dealer and most of his relatives are in that line of business.

Mr. al-Alwi's immediate relatives have made it abundantly clear to me that they are prepared to provide full emotional, financial, and medical support to Mr. al-Alwi, should he be returned to Saudi Arabia or resettled in a third country.

The family has provided ample evidence to the Board, in written and video-recorded form directly attesting to their readiness to welcome and support Mr. al-Alwi. The videos feature Mr. al-Alwi's mother, his brother, his nephews, and the family home in Jeddah, including Mr. al-Alwi's living quarters. From my experience with a number of repatriated and resettled Guantánamo prisoners since 2005, the extent and nature of the support that Mr. al-Alwi's family is prepared to provide set the ideal conditions for his release.

Thank you for taking into consideration the information I have provided. I remain at your disposal to assist with any questions you may have regarding Mr. al-Alwi.

Very truly yours

Ramzi Kassem

Associate Professor of Law

CUNY School of Law