Emergency Surgery on Iraqi at Guantánamo Reveals the Unacceptable Cruelty of the Congressional Ban on Transfers to the U.S. Mainland For Any Reason

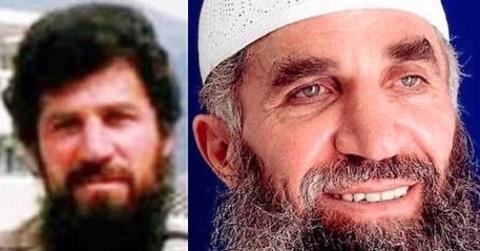

Guantánamo prisoner Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, photographed before his capture, and in a recent photo taken at the prison.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout the rest of 2022 and into 2023. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, November 30, 2022

Thanks to Carol Rosenberg of the New York Times for reporting on the latest news from Guantánamo about the troubling consequences of a Congressional ban on prisoners being taken to the U.S. mainland for any reason — even for complex surgical procedures that are difficult to undertake at the remote naval base.

The ban has been in place since the early years of the Obama presidency, when it was cynically introduced by Republican lawmakers, and has been renewed every year in the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), even though, as the prisoners grow older, some of them have increasingly challenging medical issues that are difficult to resolve at the prison, where medical teams often lack equipment and personnel found readily on the mainland.

As Rosenberg explained, "The base typically sends U.S. service members and other residents to the United States for complex care," while shamefully denying that same level of care to prisoners, who are subject to "the constraints of so-called expeditionary medicine — the practice of mobilizing specialists and equipment to Guantánamo’s small Navy hospital specifically for the prison population."

The complex medical problems of Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi

Of the 35 men still held, the one with the most complex physical problems is Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, a "high-value detainee" held at Guantánamo since 2007, when he was 46 years old, who is now 61. An Iraqi Kurd whose real name is Nashwan al-Tamir, al-Iraqi suffers from spinal stenosis, a serious and profoundly painful degenerative spinal condition, and yet, for his first ten years at Guantánamo, his condition seems to have been largely ignored by the authorities.

This is in spite of the fact that, as the Center for Victims of Torture (CVT) and Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) explained in a report in 2019, "Deprivation and Despair: The Crisis of Medical Care at Guantánamo," which I wrote about here, al-Iraqi had told Guantánamo’s medical personnel about his condition after his arrival at the prison in 2007, the medical authorities "had independently diagnosed [it] at Guantánamo in 2010," and "outside medical experts" had concluded that his condition "obviously required urgent surgical intervention."

It wasn’t, however, until September 2017 that the authorities took any action, after al-Iraqi became incontinent in his cell, having lost all feeling in his lower body. As a result, as Rosenberg reported at the time for the Miami Herald, the authorities at Guantánamo "scrambled a special neurosurgery team to the base … to conduct emergency surgery on Hadi’s lower back." Doctors consulted by defense attorneys explained that the scale of al-Iraqi’s problems had been revealed during a CT scan eight months earlier, and yet the authorities had done nothing about it.

At the time of al-Iraqi’s medical emergency, he was required by the authorities to take part in military commission hearings based on his role as a military commander for Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan in the years before his capture, but was in such pain that he had to attend in a wheelchair. His lawyers, however, were damning about the situation in which their client found himself, blaming years of "useless treatment" at Guantánamo for the situation.

Al-Iraqi underwent four more surgical procedures in less than a year, each involving a medical team brought from the U.S. mainland, but the prison authorities still insisted on making him attend his military commission hearings. As CVT and PHR explained in their report, despite his condition, the government "pushed forward with Mr. al-Tamir’s prosecution in the military commissions, which … required him to attend court on a gurney, take pain medication during legal proceedings, and sleep in the courtroom when the predictable effects of that medication set in."

They added that, "Because of Mr. al-Tamir’s fragile state, Guantánamo’s senior medical officer repeatedly recommended that [he] not be forcibly extracted from his cell to attend court proceedings … Prosecutors assured the judge in Mr. al-Tamir’s case that he did not need to issue an order to the same effect because Guantánamo’s non-medical staff would respect the recommendation. They were wrong. At the next hearing, prosecutors conceded that, in fact, Guantánamo’s non-medical commanders 'are not bound by the [senior medical officer’s] opinions nor will they defer to them in every instance.'"

Despite overseeing five operations in 2017-18, the authorities at Guantánamo conceded that al-Iraqi "may require additional surgery," suggesting, as I see it, that his condition was so severe that the compromised medical care allowed — doctors flown in, but stuck with the prison’s inadequate medical facilities — was insufficient to meet his needs.

In response to what they regarded as the inadequate treatment of al-Iraqi, his lawyers sought to persuade a U.S. court to order the government to provide "improved medical care and oversight from a civilian doctor," as Middle East Eye explained in an article in September 2021, but that request was turned down in 2019. In the meantime, his military commission case continued, even though, by that point, he "relie[d] on a wheelchair and walker inside the prison," and "also ha[d] a padded geriatric chair and a hospital bed for court, the latter of which [was] kept for when heavy painkillers cause[d] him to fall asleep," as Middle East Eye also explained.

The publication of the MEE article coincided with another medical emergency in al-Iraqi’s case, as, yet again, he "was reported to have lost feeling in his lower legs," and was "not able to walk or stand." His Pentagon-appointed civilian lawyer, Susan Hensler, told MEE, "It's my understanding that right now he can't walk."

In an emergency motion submitted by his lawyers, it was revealed that al-Iraqi had been "informed that he required specialist care," but had been told that the required treatment "was not available for several weeks."

Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi’s latest medical emergency

In fact, the required treatment doesn’t seem to have materialized at all, and it was not until 14 months later — on November 7 this year — that his condition once more deteriorated to such an extent that doctors were again flown in for his sixth emergency operation. As Carol Rosenberg explained, "A neurosurgical team fixed screws, added titanium cages and removed rods inserted into Mr. Hadi’s back in a lengthy operation on Nov. 12, according to a court filing by a prison doctor. The prisoner required blood transfusions during the procedure and suffered an unintended tear in his spinal cord. The doctor described the tear as a 'common complication' and said a neurosurgeon plugged it with a muscle graft, suture and seal."

According to Rosenberg, the account by the prison doctor "did not characterize the length of the operation, or whether it was a success," but noted instead that "the surgery team had stayed afterward to monitor the progress of the prisoner, who fainted from pain the day after the operation when military medical staff members tried to get him on his feet to begin a rehabilitation process expected to last months." Given the extent of his injuries, I have to note, trying to "get him on his feet" seems medically unsound, if not downright cruel.

In another statement submitted to the court, al-Iraqi’s lawyers noted that they had consulted a practicing neurosurgeon, who stated that he was "at risk of permanent paralysis." The neurosurgeon also pointed out that, on the U.S. mainland, "he would have been rushed into surgery the day his condition was discovered," but that the logistics of getting medical experts to Guantánamo meant a delay of five days.

The neurosurgeon’s advice chimed with opinions expressed last year by Scott Roehm of the Center for Victims of Torture, who told Middle East Eye that, "if such a medical case were taking place in the U.S., a person would see a specialist 'within hours.'" Roehm added that, "If he can't walk, he should be in a hospital, not a cell," and also explained that other prisoners "have had to carry Hadi in order for him to use the bathroom."

Roehm also noted that the Department of Defense was "either unwilling or unable, or both, to deal with these kinds of medical issues, which in some ways isn't surprising," because the prison "wasn't stood up to be a nursing home after two decades." He added that, "If the reports of what's happened here are accurate, it doesn't remotely satisfy the standard of care that all men are supposed to receive at Guantánamo."

In al-Hadi’s case, an end to his medical purgatory is supposedly in sight, although it remains to be seen if it will materialize. In June, he agreed to a plea deal in his military commission proceedings, as a result of which, as I explained at the time, he will receive a sentence capped at ten years, to be delivered in 2024, to allow the U.S. government "to find a sympathetic nation to receive him and provide him with lifelong medical care," as Carol Rosenberg explained, and also to hold him while he serves out the rest of his sentence.

In her report last week, Rosenberg noted that Susan Hensler "has been traveling overseas in search of a nation to receive him and provide him lifelong medical care," but I have to wonder how readily any third country will respond to any request to imprison al-Iraqi for eight years, and to provide him with medical care, and to note that, in the case of Majid Khan, a Pakistani national who also agreed to a plea deal regarding his involvement with Al-Qaeda, and who has been a thoroughly remorseful cooperating witness, nine months have now elapsed since his sentence ended, and yet the U.S. government has still not found a third country prepared to offer him a new home.

Just last month, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (the only official organization throughout the Americas that is empowered "to promote and protect human rights in the American hemisphere") held a hearing about Guantánamo in which lawyers not only complained about the Biden administration’s failure to release the 20 men (out of 35 in total) who have been approved for release but are still held, but also spoke specifically about the prisoners’ health needs, and the failures of the government to address them adequately.

Wells Dixon of the Center for Constitutional Rights, for example, spoke of an incident in September when one of his clients was hospitalized, telling the IACHR that the authorities "have no long-term plan of care for men like this who are approved for transfer, and continue to be detained in ill health," and calling their attitude "unacceptable" and "unconscionable."

Middle East Eye also noted that, in June this year, Corry Jeb Kucik, Guantánamo’s chief medical officer, had stated in testimony at a military commission hearing that "the only magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine that was transferred to the island, which is used for scanning the human body and providing images of a person's organs for diagnoses, has been out of service since November 2021," as an example of his concession that, "while primary care was readily available to the prison population, many more specific procedures or treatments were not possible at the base."

The case of Ammar al-Baluchi, who developed brain damage after being used as a "prop" for training in CIA "black sites"

Ammar al-Baluchi, in a photograph taken in recent years at Guantánamo.

Middle East Eye specifically noted the case of Ammar al-Baluchi, who is also seeking a hearing before the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. Another "high-value detainee," accused of involvement in the 9/11 attacks, al-Baluchi "suffer[s] from severe brain damage as a result of his treatment at CIA 'black sites,'" as Middle East Eye explained in an article last month, after speaking to one of his lawyers, Alka Pradhan, who had just returned from visiting him at Guantánamo.

Earlier this year, newly declassified documents from a 2008 CIA report revealed that, "at a secret CIA detention site in Afghanistan," after his capture in 2003, he "was used as a living prop to teach trainee interrogators, who lined up to take turns at knocking his head against a plywood wall, leaving him with brain damage," as the Guardian explained.

Pradhan told Middle East Eye that, during her last session with al-Baluchi, "his condition was so bad he wasn't able to read or form complete thoughts." As she described it, "Ammar has brain damage, stemming from his time in the black sites — and the effects of that brain damage have become really pronounced in his cognitive abilities. His ability, for example, to read documents, his ability to put together complex thoughts that would contribute to his defence, his ability to sit with us and strategise are really compromised at this point."

She added that, at Guantánamo, "there is just no hope in sight for the sort of complex medical care that he needs, both psychological and physical." To that end, she has been petitioning the District Court in Washington, D.C. to allow a Mixed Medical Commission — a panel of independent experts made up of a medical officer from the U.S. military and two doctors from a neutral country chosen by the International Committee of the Red Cross — to visit Guantánamo to assess al-Baluchi’s mental state, under Army Regulation 190-8.

Pradhan and the rest of al-Baluchi’s legal team cite a "landmark ruling" in March 2020 by Judge Rosemary Collyer of the District Court in Washington, D.C., in the case of Mohammed al-Qahtani, who was tortured at Guantánamo despite suffering from severe schizophrenia. Judge Collyer ordered an MMC to be allowed to visit and assess al-Qahtani, but in what Pradhan described as a "sloppy" and "hastily written" response under Donald Trump, Justice Department lawyers "asserted that the detainees at Guantánamo were not subject to regulation 190-8, and therefore could not receive an MMC."

As Middle East Eye added, "The Biden administration ultimately mooted the court's decision in that case by transferring Qahtani to Saudi Arabia, but Pradhan says Judge Collyer's ruling already sets the precedent for Baluchi to be independently evaluated by an outside medical team."

She also explained how "a neuropsychologist carried out an MRI of Baluchi's head in October 2018 and found 'abnormalities indicating moderate to severe brain damage' in the parts of his brain affecting memory formation, retrieval, and behavioural regulation," how, "According to another neuropsychologist's evaluation of Baluchi in early 2020, [his] psychological functioning had 'seriously diminished' as a result of the torture, leaving him with a host of issues including traumatic brain injury, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder," and how another MRI scan in 2021 revealed that "a spinal lesion in his back had grown at an alarming rate," as Pradhan described it. However, as MEE added, "with the base's MRI machine now broken, medical staff are not able to assess the condition or diagnose the lesion."

However, despite the clear rationale for al-Baluchi to be allowed a visit by a Mixed Medical Commission, the Biden administration continues to resist its implementation. As Pradhan said, "I really do not understand why they are putting up such a fight on this which really undermines what the left hand is doing, trying to very slowly find a way to close Guantánamo." Asked to comment, Scott Roehm added, "If the goal is to close Guantánamo, and a mixed medical commission is to conclude that this person is so sick, debilitated, injured, etc., that they have to be repatriated, that facilitates closure."

In all likelihood, the Biden administration’s resistance, in al-Baluchi’s case, is because plea deals are ongoing in his case, and that of the four other men accused of involvement in the 9/11 attacks, in an attempt to break the 14-year deadlock since they were first charged under George W. Bush, and officials therefore don’t want anything to undermine these negotiations. However, in Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi’s case, a plea deal has already been reached, and as a result, the government’s position — which seems to amount to nothing more than crossing their fingers and hoping that permanent paralysis can be avoided before his sentencing in 2024 — seems particularly unacceptable.

The National Defense Authorization Act

On this front, it would be helpful if the restriction on bringing prisoners to the U.S. mainland for any reason were to be dropped from this year’s National Defense Authorization Act, but, yet again, it is almost certain, as the Senate and House Armed Services Committees work to consolidate a bill for next year, that that will not happen.

In June, the House version of the NDAA upheld the existing ban on the release of any prisoners to Libya, Somalia, Syria or Yemen — with Afghanistan added in an amendment — although, reflecting Democrats’ narrow control of the lower chamber, as a summary explained, it did "not include the arbitrary statutory prohibitions on transfer of detainees out of the detention facility at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, that hinder progress toward its closure," leaving open, therefore, the possibly of transfers to the U.S. mainland, including for urgent medical care.

In the Senate, however, where, as The Hill explained, "Democrats [would] need GOP support to pass the defense funding bill," a move that would face "a wall of opposition from Republicans," the final version of the bill duly retained the full array of Republican-backed prohibitions that have done so much to impede efforts to close Guantánamo over many years — "a ban on the transfer of Guantánamo detainees to the United States" for any reason, as well as "a ban on the use of DoD funds to construct or modify facilities in the United States to house Guantánamo detainees," and, as in the House version, a ban on releasing prisoners to Libya, Somalia, Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan.

After the midterms, with Democrats losing the House but securing control of the Senate, it may be that next year’s NDAA will finally provide an opportunity for the ban on bringing prisoners to the U.S. mainland for any reason to be lifted, but, even if that happens, it leaves Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi reliant on visiting doctors for another year, left only to hope that his condition doesn’t deteriorate so severely that he is left permanently paralyzed — and that, I should hardly need add, is a shameful situation for the U.S. government to be defending.