The Horrors of Guantánamo Eloquently Explained By A High School Teacher to Readers of Teen Vogue

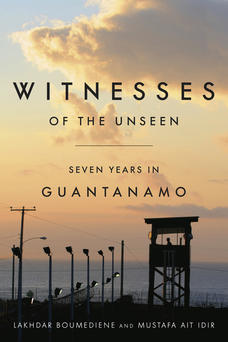

The cover of 'Witnesses of the Unseen: Seven Years in Guantánamo', which former prisoners Lakhdar Boumediene and Mustafa Ait Idir wrote with U.S. history teacher Dan Norland.

By Andy Worthington, May 22, 2018

Last week, a powerful and eloquent condemnation of the prison at Guantánamo Bay was published in Teen Vogue. As a lawyer friend explained, "For the past couple of years, Teen Vogue has been doing a fantastic job reporting on political and social issues — their election and Muslim ban coverage was and is excellent."

The article, which we’re cross-posting below in the hope of reaching a slightly different audience, was written by Dan Norland, a high school history teacher who knows how to talk to young people, and who, like Teen Vogue’s editors, understands that young people are often much more capable of critical, open-minded thought than their elders — something I perceived in relation to Guantánamo many years ago, as discussed in my 2011 article, The 11-Year Old American Girl Who Knows More About Guantánamo Than Most U.S. Lawmakers.

Dan is not only a high school teacher; he also helped two former Guantánamo prisoners — two Algerians kidnapped in Bosnia in 2002 in connection with a completely non-existent terrorist plot — write a searing account of their imprisonment and torture, Witnesses of the Unseen: Seven Years in Guantánamo, which was published last year, and for which I was delighted to have been asked by the publishers to write a review, which I did.

In my review, I wrote, "Lakhdar Boumediene and Mustafa Ait Idir are two of the most notorious victims of the U.S.’s post-9/11 program of rendition, torture, and indefinite detention. Kidnapped on groundless suspicions, they are perfectly placed to reflect on the horrors of Guantánamo and the 'war on terror.' With a warmth and intelligence sadly lacking in America's treatment of them, this powerful joint memoir exposes their captors' cruelty and the Kafkaesque twists and turns of the U.S. government's efforts to build a case against them."

In his op-ed, with reference to Lakhdar Boumediene and Mustafa Ait Idir, Dan Norland concisely explains why Guantánamo is such a shameful, brutal and lawless place, and why it must be closed. Sadly, as he notes, polls indicate that "more than half of Americans are content to continue with business as usual in Guantánamo. For the most part Americans just look away, in part because of the media maelstrom that is the Trump era, and in part because it’s so much easier. Our collective blindness protects us from truths we might not be able to handle and problems too painful to face."

Yesterday marked Guantánamo’s 5,975th day of existence, and on June 15 the prison will have been open for 6,000 days. We’re planning something of a media blitz to mark 6,000 days, and hope you’ll join us by printing off a poster telling Donald Trump how long Guantánamo has been open and urging him to close it, taking a photo with it, and sending it to us. All the photos we’ve received so far this year are here.

Below is Dan Norland’s op-ed. We hope you have time to read it, and that you’ll share it if you appreciate it.

Guantánamo Bay, Explained

By Dan Norland, Teen Vogue, May 16, 2018

"I think all Americans should know what our country has done and to whom."

In this op-ed, high school history teacher Dan Norland explains why it's important that young people in the United States understand the significance of Guantánamo Bay. Norland discusses the military base with his students at La Jolla Country Day School in San Diego, California.

"Raise your hand," I tell my ninth-grade history class, "if you’ve heard of Guantánamo."

A few hands inch upward, but most of the students keep their hands rooted to their desks. No one has ever talked to them about what the United States did — and is doing — in Guantánamo Bay, in the southeast corner of Cuba.

But it’s a conversation we ought to have. In the months since the Parkland shooting and subsequent displays of activism calling for an end to gun violence, teenagers have been proving that they have the capacity to start stitching together our nation’s broken seams, if only we’ll let them.

So I teach my students about Guantánamo, where the U.S. government has maintained a naval base for decades, against Cuba’s wishes. It’s where, in early 2002, we built a prison for alleged terrorists, and in that year held nearly 800 men and children, all Muslim, ranging from possible 9/11 plotters to goat herders whose neighbors falsely identified them as Al Qaeda members in exchange for a $5,000 bounty from the U.S.

And then I tell them the specific stories of two innocent men who were tortured there.

I met Lakhdar Boumediene and Mustafa Ait Idir in 2011, a few years after they won their freedom from Guantánamo. A federal judge had reviewed the supposed evidence against them in 2008 and determined that the government had no basis to lock them up. Lakhdar and Mustafa had gotten their day in court, and not long thereafter they were free.

The problem, however, was that getting their day in court took Lakhdar and Mustafa the better part of seven years. They had to take their case, Boumediene v. Bush, all the way to the Supreme Court just to get the right to argue their case before a federal judge. Even though the Constitution grants that right, known as habeas corpus, to everyone detained on American soil, the Bush administration argued that Guantánamo doesn’t count because the facility is technically only rented from the Cuban government.

The government’s attempt to circumvent habeas corpus — to build a prison outside the reach of the law — very nearly succeeded. Had it not been for a law firm’s willingness to spend more than 35,000 hours on Lakhdar and Mustafa’s case — work that would have cost paying clients an estimated $17 million — they would likely still be in Guantánamo. Lakhdar’s eldest daughter would still be writing letters to her wrongly imprisoned father, and his two youngest children(two youngest children) would never have been born.

The tragedy of Lakhdar and Mustafa’s case is not just that they were wrongly held for seven years, but also what was done to them during that time. In the early months of Guantánamo, while the prison was still being built, they were held outside in scorpion-infested cages with gym mats to sleep on and buckets to use instead of toilets. Once the prison was built and interrogations began, they were subjected to brutal beatings for refusing to confess to crimes they didn’t commit or to testify against men they didn’t know. They suffered from systematic sleep deprivation — Lakhdar was kept awake for more than two weeks straight — as well as threats of sodomy, assaults on their religion, and the fear, provoked by interrogators, that they would never see their families again. When journalist Jake Tapper of CNN asked Lakhdar in a 2009 interview if he thought he had been tortured, Lakhdar replied, "I don’t think. I’m sure."

And yet, remarkably, Lakhdar and Mustafa did not let their experience break them. I had the honor of helping them write a book about their ordeal, Witnesses of the Unseen: Seven Years in Guantánamo. Getting to know these men and their stories was moving and deeply inspiring. They somehow endured years of unjust imprisonment and torture, yet never lost the capacity to be fundamentally decent and kind.

I share Lakhdar and Mustafa’s stories with my students in part because I think everyone can learn from their resilience and grace, but also because I think all Americans should know what our country has done and to whom. Whether my students agree with President Donald Trump that Guantánamo should remain open and we should "load it up" with more prisoners is, of course, up to them. But I want them to pay close attention to the facts so they can evaluate the arguments for themselves and arrive at fully informed conclusions. Decisions about the future of human rights in America should not be made by default. We cannot let Guantánamo, and the people we imprison there, go unseen.

Shortly after Witnesses was published in April 2017, Lakhdar was asked in an interview what he wanted readers to take away from his book. "I want Americans to know," he answered, "that Guantánamo happened not to monsters, but to men." Days later, I came across his quote on Twitter, followed by this eloquent reply: "WHO F*CKING CARES?"

It’s easy to dismiss that as the heartless rant of a Twitter troll, which it is. But it’s also official U.S. policy: Lakhdar and Mustafa have never received an apology or even an explanation from the American government, let alone compensation. Not a single former detainee has.

Right now, 40 men remain in Guantánamo, "forever prisoners" who may never have a meaningful opportunity to argue their innocence. (One man was released to Saudi Arabia on May 2, months after he was supposed to be resettled under the terms of a plea deal he had signed years before.) Polling suggests that more than half of Americans are content to continue with business as usual in Guantánamo. For the most part Americans just look away, in part because of the media maelstrom that is the Trump era, and in part because it’s so much easier. Our collective blindness protects us from truths we might not be able to handle and problems too painful to face.

It also prevents us from solving them.

We can no longer afford to look away, if ever we could. As engaged citizens in a fragile democracy, we need to be vigilantly, persistently attentive. Perhaps now more than ever, it’s critical that we don’t treat "WHO F*CKING CARES" as a rhetorical question.

I f*cking care. And I hope you do too.