In Contentious Split Decision, Appeals Court Upholds Guantánamo Prisoner Ali Hamza Al-Bahlul’s Conspiracy Conviction

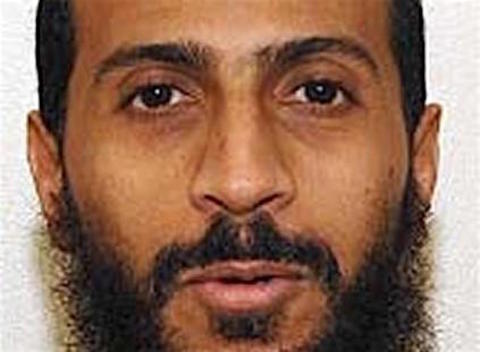

Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, in a photo from the classified military files from Guantánamo that were released by WikiLeaks in 2011.

By Andy Worthington, October 28, 2016

Last week, in the latest development in a long-running court case related to Guantánamo, the court of appeals in Washington, D.C. (the D.C. Circuit) upheld Ali Hamza al-Bahlul’s November 2008 conviction for conspiracy in his trial by military commission, but in a divided decision that means the case will almost certainly now make its way to the Supreme Court.

Al-Bahlul, a Yemeni, was seized in Afghanistan in December 2001, and taken to Guantánamo, where, in June 2004, he was charged in the first version of the military commissions that were ill-advisedly dragged out of the history books by the Bush administration in November 2001, primarily on the basis that he had made a promotional video for al-Qaeda.

Two years later, the commissions were scrapped after the Supreme Court ruled that they were illegal, but they were subsequently revived by Congress, and in February 2008 he was charged again, and convicted in November 2008, after a trial in which he refused to mount a defense, on "17 counts of conspiracy, eight counts of solicitation to commit murder and 10 counts of providing material support for terrorism," as I described it at the time.

However, in October 2012, the D.C. Circuit Court threw out the material support conviction against another prisoner, Salim Hamdan, a driver for Osama bin Laden, and in January 2013 al-Bahlul’s conviction was also dismissed. As I explained at the time, "the Court of Appeals vacated his conviction for material support, conspiracy, and another charge, solicitation, citing a supplemental brief filed by the government on January 9, 2013, advising the Court that it took the 'position that Hamdan requires reversal of Bahlul’s convictions by military commission.'"

Nevertheless, the government appealed to the full court, rather than just the three judges who reached the ruling in January 2013. That hearing took place on September 30, 2013, leading to what I described as “the rather confusing outcome of the government’s appeal” after the ruling was delivered on July 14, 2014.

The en banc court, as I also described it, "confirmed that al-Bahlul’s material support conviction was overturned, and also confirmed that his conviction for soliciting others to commit war crimes was overturned as well." The judges, as I put it, "agreed that providing material support for terrorism is not a war crime triable by military commission based on conduct occurring prior to 2006, even for a defendant who gave up that argument at trial" — and the same applied to the solicitation charges.

However, "on the third count on which he was initially convicted, conspiracy to commit war crimes, the D.C. Circuit Court rejected a constitutional challenge brought by al-Bahlul, but did so, as the National Law Journal explained, in 'a fractured ruling that left unclear how future cases against terrorism suspects might proceed.'"

Revealing quite how "unclear" the ruling was, aspects of al-Bahlul’s conspiracy conviction were sent back to the original three-judge panel, and on June 12, 2015, the court "vacated Bahlul’s inchoate conspiracy conviction," as the Harvard Law School National Security Journal explained, for reasons related to the conflict between federal courts (Article III courts), where material support and conspiracy are crimes, and military commissions, where they are not (or were not until Congress tried to claim that they were, in 2006 and again in 2009).

The court held that, as the Harvard article described it, "1) the claim that Congress encroached upon Article III judicial power by authorizing Executive Branch tribunals to try purely domestic crime of inchoate conspiracy was a structural objection that could not be forfeited and 2) conviction of Bahlul for inchoate conspiracy by law of war military commission violated separation of powers enshrined in Article III."

The government then petitioned for another en banc hearing, arguing that Congress "did not violate Article III when it codified conspiracy as an offense triable by military commission," because:

The Constitution confers on Congress extensive war powers that include not only the power to "define and punish . . . offenses against the Law of Nations," but also the power to declare war, as well as the power to "make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers." Congress’s authority to give military tribunals jurisdiction to try alien unlawful enemy combatants for conspiracies to commit war crimes derives from all of these sources.

The court granted the government’s petition, whilst also "vacat[ing] its June 2015 judgment that vacated Bahlul’s conspiracy conviction." That hearing took place on December 1, 2015, leading to last week’s ruling, by six judges to three, reinstating al-Bahlul’s conspiracy conviction.

As the Center on National Security at Fordham Law School explained in its morning brief the day after the ruling, "Th[e] issue in the case was whether the Constitution allows Congress to make conspiracy to commit war crimes an offense triable by military commissions, despite the fact that conspiracy is not recognized as an international war crime. Four of the six judges in the majority argued that Congress had the constitutional power to authorize conspiracy charges in the military commission. One of the four judges, Brett Kavanaugh, wrote that 'wherever one might ultimately draw the outer boundaries of Congress’s authority to establish offenses triable by military commission, the historically rooted offense of conspiracy to commit war crimes is well within those limits.'"

The morning brief added, "However, the ruling lacked a clear majority, as the two other judges who voted to uphold the decision did so for different legal reasons. In dissent, three judges wrote that 'although the government might well be entitled to detain al-Bahlul as an enemy belligerent, it does not have the power to switch the Constitution on and off at will.' They added that Bahlul’s prosecution on conspiracy charges 'exceeded the scope' of what is allowed for military tribunals under the Constitution."

The Fordham briefing also noted that Michel Paradis, one of al-Bahlul’s attorneys, "said he expected the next step, after consulting with his client, was to attempt to have the case heard by the Supreme Court."

In the New York Times, Charlie Savage explained how the ruling "salvag[ed] a rare successful outcome for the troubled tribunals system," but added that "the divided ruling left unresolved a broader legal question that could help determine whether the tribunals system takes root as a permanent alternative to civilian court for prosecuting terrorism suspects, or fades away after the handful of current cases come to an end."

Savage added, "That question is whether the military commissions can be used to prosecute additional terrorism defendants for conspiracy. That charge, which is useful for trying people suspected of participating in a terrorist organization, is considered a crime under domestic law, but it is not a war crime recognized by international law. Generally, tribunals are used to prosecute war crimes."

Steve Vladeck, a law professor at the University of Texas, told Charlie Savage, "There is still no resolution of this basic constitutional question that has been dogging the commissions since their inception. The court let this one conviction stand, but in the process, it didn’t actually settle the fight."

Savage also explained a little more about the ruling, noting that "[f]our of the six judges in the majority — Janice Rogers Brown, Thomas B. Griffith, Brett Kavanaugh and Karen L. Henderson, all of whom were appointed by Republican presidents — argued that Congress had the constitutional power to authorize bringing conspiracy charges in the war crimes court, despite international law," while "the other two judges in the majority — Patricia Ann Millett and Robert L. Wilkins, both Democratic appointees — agreed that Mr. Bahlul’s conviction should be upheld, but cited different legal reasons specific to his case. They expressed no opinion about the broader issue of conspiracy charges."

The three dissenting judges were Cornelia T.L. Pillard, Judith W. Rogers and David S. Tatel, all Democratic appointees, who, as Charlie Savage described it, "said conspiracy charges could never be brought in a commission." He added, "As a result, there was no majority to resolve the bigger question about such charges."

Note: Steve Vladeck is also the co-editor-in-chief of the very worthwhile Just Security, and also sometimes writes for the generally to be avoided Lawfare, which positions itself as a centrist forum for national security discussions but is actually, in general, rather disturbingly right-wing. Nevertheless, those who want to know more about the intricacies of this latest ruling — and can understand them — are directed to Steve’s latest post, “Al Bahlul and the Long Shadow of Illegitimacy.”